Zika Virus: An Emerging Health Threat

Predicted distribution of Ae. aegypti

Predicted distribution of Ae. albopictus

Credit: Kraemer et al. eLife 2015;4:e08347

For decades, the mosquito-transmitted Zika virus was mainly seen in equatorial regions of Africa and Asia, where it caused a mild, flu-like illness and rash in some people. About 10 years ago, the picture began to expand with the appearance of Zika outbreaks in the Pacific islands. Then, last spring, Zika popped up in South America, where it has so far infected more than 1 million Brazilians and been tentatively linked to a steep increase in the number of babies born with microcephaly, a very serious condition characterized by a small head and brain [1]. And

Zika’s disturbing march may not stop there.

In a new study in the journal The Lancet, infectious disease modelers calculate that Zika virus has the potential to spread across

warmer and wetter parts of the Western Hemisphere as local mosquitoes

pick up the virus from infected travelers and then spread the virus to

other people [2]. The study suggests that Zika virus could eventually

reach regions of the United States in which 60 percent of our population

lives. This highlights the need for NIH and its partners in the public

and private sectors to intensify research on Zika virus and to look for

new ways to treat the disease and prevent its spread.

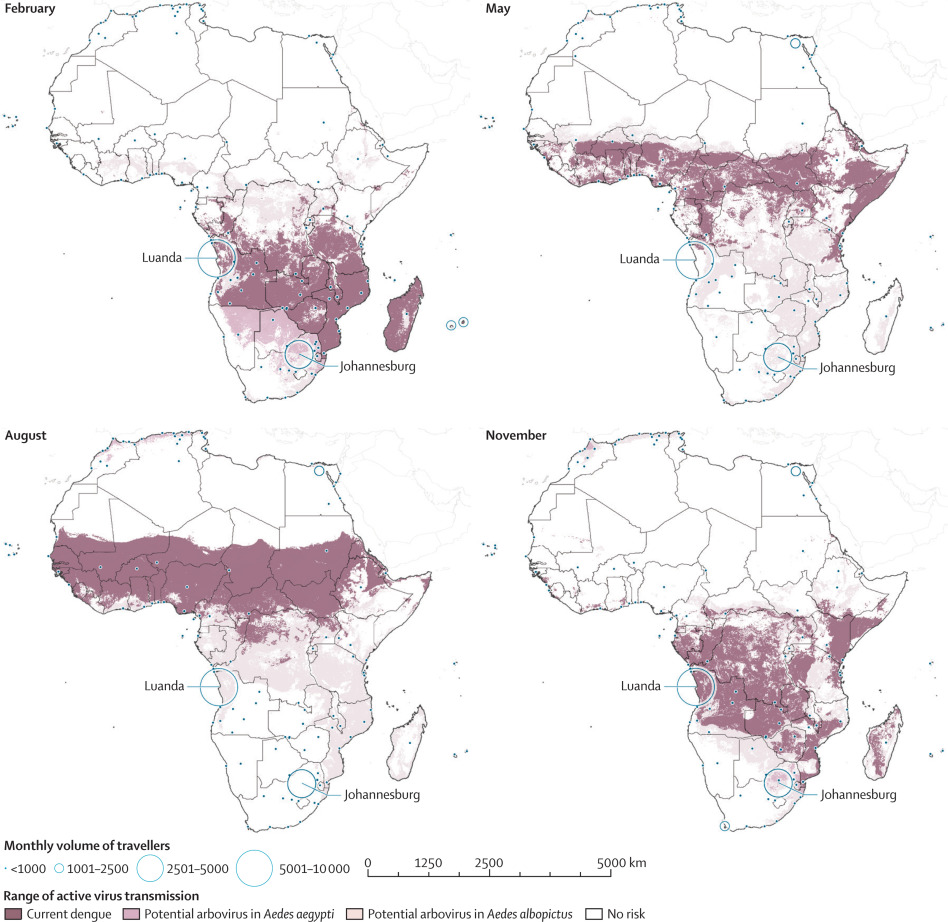

Zika virus infection can be spread by yellow fever mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti), and experimental evidence suggests the virus also can be transmitted by Asian tiger mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus). Aedes mosquitoes – already

known for transmitting other viral illnesses, such as dengue and

chikungunya – have a wide and expanding global distribution, including in

the United States [3]. To predict places around the world where Zika

virus might spread as people infected in the Brazilian outbreak come

into contact with biting Aedes mosquitoes, the NIH-supported

research team, led by Kamran Khan of St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto,

first mapped the global distribution of Aedes mosquitoes along

with the climate conditions the researchers deemed favorable to the

spread of Zika virus. They then layered onto this map the final

destinations of travellers who might have been exposed to Zika virus

before departing Brazil from September 2014 to August 2015.

During the year, 9.9 million travelers left 146 Brazilian airports

near areas known to be conducive to Zika virus transmission for

destinations around the world. North and South American countries were

the most-popular destinations (representing 65 percent of travelers)

followed by those in Europe (27 percent) and Asia (5 percent). The

most-popular travel spot was the United States, with more than 2.7

million people making the trip.

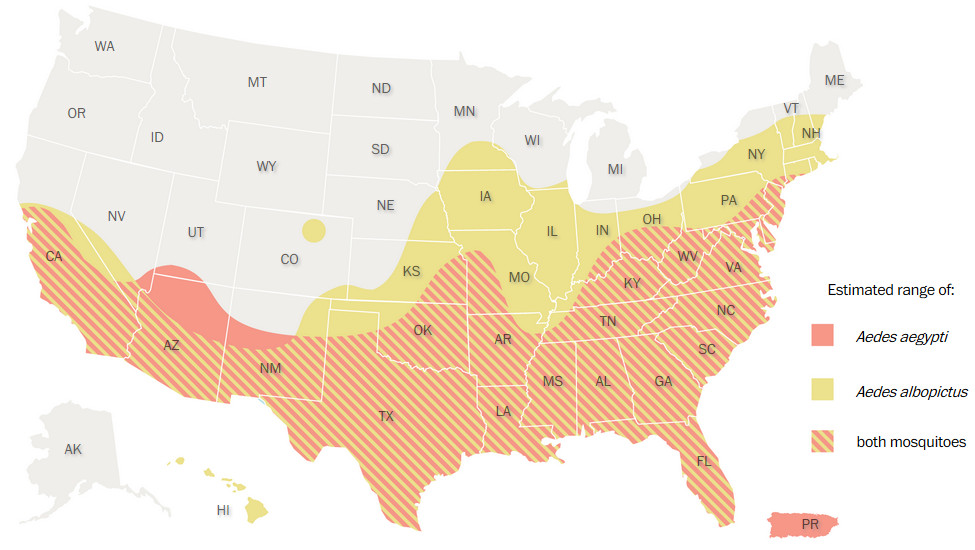

According to the researchers’ calculations, about 200 million

Americans – more than 60 percent of the population—reside in areas of the

United States that might be conducive to the spread of Zika virus during

warmer months through biting mosquitoes, including areas along the East

and West Coasts and much of the Midwest. In addition, another 22.7

million people live in humid, subtropical parts of the country that

might support the spread of Zika virus all year round, including

southern Texas and Florida. Already, there are reports of local spread

of the virus within Puerto Rico and of travelers returning to the U.S.

with the Zika infection.

With all this in mind, it is now critically important to confirm,

through careful epidemiological and animal studies, whether or not a

causal link exists between Zika virus infections in pregnant women and

microcephaly in their newborn babies. Brazilian health authorities made

the initial connection between the virus and birth defects, primarily

because the increase in microcephaly seemed to emerge a few months after

the introduction of Zika virus into Brazil. Thousands of cases of

microcephaly have now been reported and the Brazilian health ministry

has confirmed the presence of Zika virus in tissue samples and amniotic

fluid collected from a small number of affected children or their

mothers [1]. While the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) has obtained similar findings, it remains unclear what other

factors might increase risks to the developing fetus [4].

In November, health authorities in French Polynesia also reported an

unusual increase of central nervous system malformations in fetuses and

infants that seemed to coincide with the Zika outbreak there. And, last

week, came news reports of the first child born in the U.S. with

microcephaly possibly linked to Zika. The child’s mother had lived in

Brazil during her pregnancy before moving to Oahu, Hawaii [5]. As an

additional concern, there are reports in French Polynesia and Brazil of a

possible connection between Zika infection and Guillain-Barré syndrome,

a mysterious condition in which the immune system attacks part of the

peripheral nervous system [1].

With no vaccine or treatment currently available to prevent or treat

Zika infection, the best way for individuals—and pregnant women in

particular—to protect themselves is to avoid traveling to places where

Zika is known to be spreading. If an individual has to live or work in

such a region, CDC recommends strict precautions to avoid mosquito

bites, including wearing protective clothing, using insect repellants,

and sleeping in rooms with window screens or air conditioning. Though

still unproven, the link between Zika infection and microcephaly has

also prompted CDC to issue interim guidelines recommending that women

who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant consider postponing

travel to areas where Zika virus has spread. This frequently updated

list currently includes Puerto Rico, Mexico, and 20 other countries in

South America, Central America, the Caribbean, the Pacific islands, and

Africa [6].

Many important questions remain about Zika. But, as Anthony Fauci,

director of NIH’s National Institute for Allergy and Infectious

Diseases, noted in his recent New England Journal of Medicine

essay, one thing is very clear: far more research into Zika virus and

its interactions with its mosquito, human, and non-human primate hosts

is urgently needed [7]. For instance, it will be important to determine

how readily Asian tiger mosquitoes, which can tolerate relatively cold

temperatures, spread Zika virus.

The scientific community must also step up its efforts to develop

innovative approaches against the virus, and that’s certainly happening

at NIH. With NIAID taking the lead, research is underway to understand

better Zika’s effects on the body, to develop diagnostic tests to

identify the virus rapidly in people, and to ramp up testing of

therapeutics that might be effective. Importantly, NIAID researchers

already are working on vaccine candidates to prevent Zika virus from

infecting people. All of this work is a compelling example of NIH

mobilizing swiftly in the face of a rapidly emerging infectious disease,

and seeking the research answers that Americans and people across the

globe need.

References:

[1] Rapid risk assessment: Zika virus epidemic in the Americas: potential association with microcephaly and Guillian-Barre syndrome. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 10 December 2015.

[2] Anticipating the international spread of Zika virus from Brazil.

Bogoch II, Brady OJ, Kraemer MU, German M, Creatore MI, Kulkarni MA,

Brownstein JS, Mekaru SR, Hay SI, Groot E, Watts A, Khan K. Lancet. 2016

Jan 14. pii: S0140-6736(16)00080-5.

[3] The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus.

Kraemer MU, Sinka ME, Duda KA, Mylne AQ, Shearer FM, Barker CM, Moore

CG, Carvalho RG, Coelho GE, Van Bortel W, Hendrickx G, Schaffner F,

Elyazar IR, Teng HJ, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Pigott DM, Scott TW, Smith

DL, Wint GR, Golding N, Hay SI. Elife. 2015 June 30;4:e08347.

[4] CDC Telebriefing: Zika Virus Travel Alert. Centers for Disease Control. 15 January 2016.

[5] Hawaii baby born with small head had prior Zika infection. CNN. 19 January 2016.

[6] Interim Guidelines for Pregnant Women During a Zika Virus Outbreak — United States, 2016. Centers for Disease Control. 19 January 2016.

[7] Zika Virus in the Americas – Yet Another Arbovirus Threat. Fauci AS, Morens DM. N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 13. [Epub ahead of print]

Links:

Zika Virus Infection and Pregnancy (CDC)

Kamran Khan (St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto)

Fogarty International Center (NIH)

NIH Support: Fogarty International Center

Related posts:

– All the known cases of Zika virus in the World

– Where in the World is Zika virus?

– Mapping the Zika Virus

– The Zika virus

– Zika virus threatens US from abroad