Why So Many Cultures Still Fear the “Evil Eye”

The idea that someone’s jealous look could make you sick, ruin your luck, or even put your child in danger has been around for thousands of years. This is what people mean when they talk about the “evil eye.” Unlike witchcraft or spells, it’s often unintentional – the harm comes from envy itself. Ancient references show up in Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, and across Jewish, Islamic, Hindu, and Christian traditions.

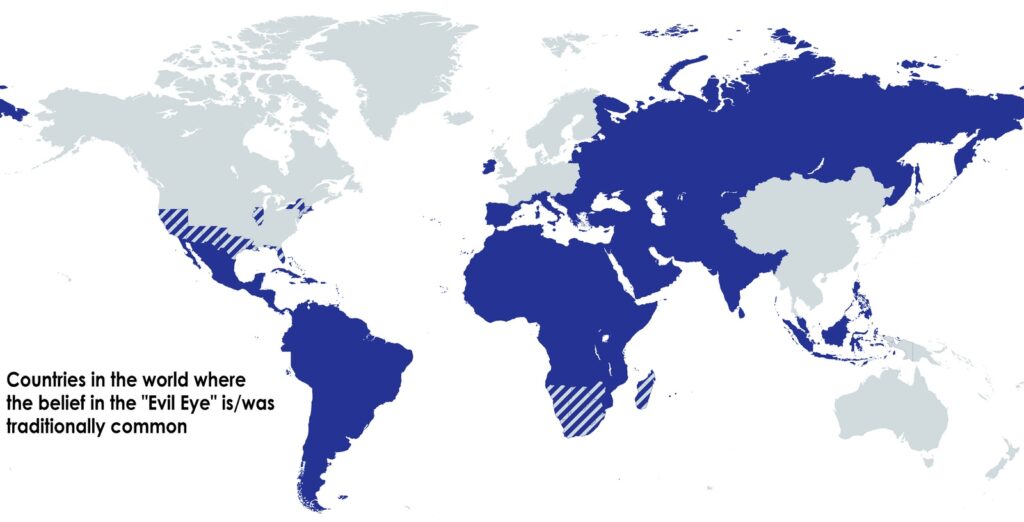

The map below, created by Reddit user Simple_Pension_1330, shows just how widespread this belief once was. Huge areas of the Mediterranean, the Middle East, South Asia, Africa, and Latin America are shaded in. But notice what’s missing: much of Northern Europe, North America, Japan, and Australia.

So why did so many societies develop this idea in the first place? Anthropologists suggest it comes down to envy and social balance. In smaller or traditional communities, showing off wealth, beauty, or success could upset others. The “evil eye” became a way of naming that threat, and rituals grew up to guard against it. The American folklorist Alan Dundes even linked it to the idea of “limited good”: the belief that there’s only so much fortune to go around, so one person’s gain must mean someone else’s loss.

The protective customs themselves vary a lot. In Turkey and Greece, you’ll see the familiar blue glass beads called nazar or mati, still sold in markets and airports today. In southern Italy, people carry little horn-shaped charms called cornicelli, and some families still perform rituals with olive oil drops in water to check if someone has been cursed. In Mexico and Central America, el mal de ojo is said to make babies sick, so parents tie red strings or special seeds around their wrists for protection. In South Asia, families put a small black dot on a child’s forehead or use charms called nazar battu to keep away jealous looks. The Philippines has something similar called usog, where a stranger’s greeting is thought to harm a baby; the cure is for the person to put a bit of saliva on the child’s forehead while saying protective words. And in Ethiopia, whole groups of people once carried the suspicion of buda, or evil power, so protective beads and charms were used to ward them off.

Some of these traditions sound unusual to modern ears. In India, artisans would deliberately weave small flaws into fabrics so they wouldn’t draw dangerous envy. In parts of Ethiopia, highly skilled craftsmen were seen as suspicious, as though their talent must come from evil powers. In southern Europe, mothers whispered prayers over bowls of water to protect babies from a dangerous gaze.

Looking back at the map, it’s interesting that the belief seems weaker in many developed nations. Northern Europe, Japan, and most of North America show little sign of it, at least in their mainstream culture. This probably has to do with different worldviews. Societies built on ideas of abundance and growth don’t see envy as such a cosmic threat, and modern medicine and education have replaced a lot of old folk explanations.