The Adriatic Tunnel: When Czechoslovakia Dreamed of Boring Through Austria

Countries without coastlines get the short end of the stick. Switzerland figured out how to make it work, but they’re special. Most landlocked nations spend half their time begging neighbors to let goods pass through. Your steel sits at some border guard’s whim. Prices go up because every shipment has to cross multiple countries. And when it comes to throwing your weight around internationally? Forget it. No navy, no major shipping routes, no real influence.

Czechoslovakia was fed up with this by the 1970s. Czech factories were cranking out quality machinery and steel, but getting it to overseas markets meant endless bureaucracy and delays. Rail cars would sit for days waiting for customs clearance, then sit some more at the next border. It was maddening.

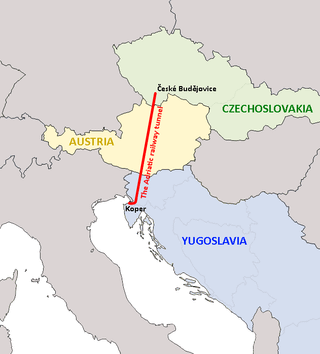

Karel Žlábek, a professor working with the design institute Pragoprojekt, had enough of watching this nonsense. His solution? Forget the neighbors entirely. Dig a railway tunnel from České Budějovice straight to the Adriatic Sea – 410 kilometers (255 miles) of it.

Most of the route would burrow under Austria for 350 kilometers (217 miles), cutting through the Alps before popping out at Koper in Yugoslavia. They’d build an artificial island called Adriaport at the end, complete with cargo docks and beaches where Czech families could finally take seaside vacations.

Žlábek wasn’t completely crazy. His engineers planned three tunnel segments connected by vertical shafts every few kilometers for ventilation and emergency access. Maintenance crews could reach problems without traveling the entire route. They even wanted to drive trucks directly onto trains for door-to-door delivery.

Then someone did the math. 258 billion Czechoslovak crowns in 1979 money – about €177 billion today. That killed it right there.

Even if they’d found the cash, getting permission would have been a nightmare. Austria was neutral, Yugoslavia did its own thing, and neither wanted to deal with Moscow’s opinions about major construction projects. Convincing them to let Czechoslovakia tunnel under Austrian mountains and emerge on Yugoslav territory? Good luck with that.

The whole thing stayed on paper. By 1993, when Czechoslovakia peacefully split up, Žlábek’s tunnel was ancient history. Turned out the problem solved itself anyway – both new countries eventually joined the EU and got access to plenty of ports without digging through mountains.

Those original blueprints are still somewhere in Prague’s archives. They’re a reminder that when geography boxes you in, humans dream big. Maybe impossibly big.

But sometimes the simple solution – like joining a trade bloc – works better than drilling through half of Europe.