Mapping the Disappearance of Norway’s Untouched Forests

In the early 20th century, Norway’s landscapes were shaped more by glacial erosion than by roads. That began to change with industrialization, logging expansion, and especially post-WWII development. Roads, power lines, cabins, and hydroelectric projects fragmented the wilderness.

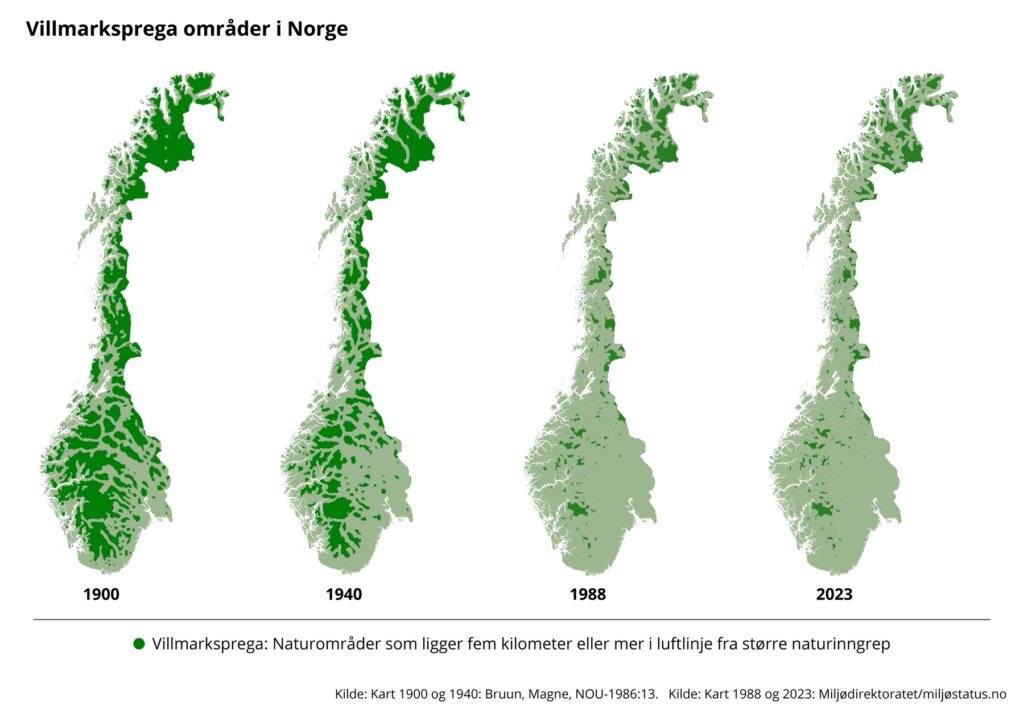

The maps below, created by the Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management, show the untouched forests of the country in 1900, 1940, 1988, and 2023.

Between 1900 and 1988, the loss was rapid and extensive. By 1988, the vast green blotches of unbroken land had shrunk to fragments.

Since then, something noteworthy has occurred: the pace of loss has slowed. From 1988 to 2023, the total area of land meeting the “villmarkspreget” (untouched, primary forests) criteria has not declined significantly. This relative stabilization is partly due to stronger land-use policies, protected area designations, and reduced infrastructure expansion in remote areas.

At the same time, Norway’s total forest area, according to the World Bank, has actually increased slightly since 2010, mostly through reforestation and improved forest management. But these gains do not restore the wilderness that was lost. Newer forests are often monocultures or managed stands and lack the complexity and biodiversity of old-growth ecosystems.

Moreover, wilderness isn’t just defined by the presence of trees or animals—it’s defined by distance. Distance from roads, noise, lights, and people. Distance that allows ecosystems to operate on their own terms.

Today, even in a country as forested as Norway, it’s nearly impossible to find a location more than five kilometers from some form of human intervention. That ecological distance has vanished.

The Global Lesson: Who Bears the Burden of Conservation?

This trend in Norway raises an uncomfortable but necessary question: If even a wealthy, low-population country with strong environmental regulations could not preserve its wilderness, what are we asking of developing countries?

Take Brazil, for example. It still has large areas of intact tropical rainforest—especially in the Amazon—but it is under constant pressure from agriculture, mining, and infrastructure development. Between 2001 and 2023, Brazil lost nearly 69 million hectares of tree cover, according to Global Forest Watch. And yet, global conservation demands are often directed at countries like Brazil to preserve what developed nations did not.

During the peak of their economic development, countries like Norway, the United States, and Germany cleared forests, dammed rivers, and built road networks with little concern for long-term ecological fragmentation. Now that those gains have been secured, the burden of restraint is shifted elsewhere.

This double standard lies at the heart of many global environmental tensions. We expect developing nations to restrict their growth in ways that richer nations never did—and we often do so without acknowledging this history.