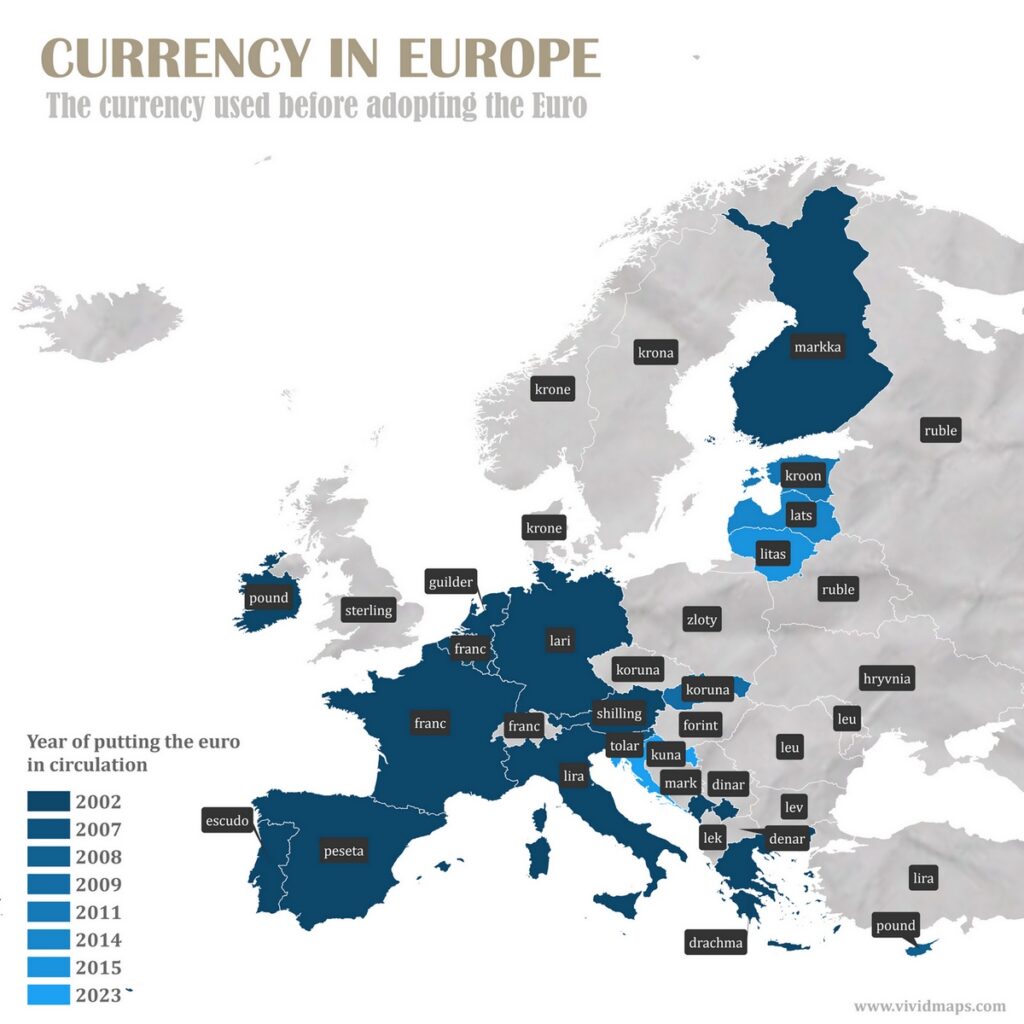

Which Currencies Did European Countries Use Before the Euro?

Until the late 1990s, crossing Europe meant juggling several kinds of money. You might pay for lunch in francs, fill your car with marks, and buy a train ticket in lira or pesetas. Each border crossing brought a new exchange rate and the quiet worry of miscounted bills. For anyone traveling or doing business between countries, it was a small but ever-present inconvenience.

The idea of a shared European currency had been discussed for many years, but it only began to take real form toward the end of the twentieth century. Attempts in the 1970s to keep currencies stable were quickly undone by inflation and political uncertainty. It took a different generation of leaders and a stronger, more integrated European Union to move the plan forward finally. The Maastricht Treaty, signed in 1992, set the groundwork for creating a single European currency and outlined the framework that would become the Economic and Monetary Union.

Three years later, in December 1995, European leaders meeting in Madrid agreed to call the new currency the ‘euro’ (ECB). They settled on it because it was short, neutral, and worked easily in every European language. Soon after, the first designs for notes and coins were approved — images of arches and bridges meant to stand for openness and unity rather than any single country or culture.

The euro came into existence on 1 January 1999, though at first it was used only electronically. Banks and companies began working with it immediately, even while people still handled their old national currencies day to day. On that first day, eleven countries joined together: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. Their exchange rates were fixed definitively to the euro, ending decades of national currency fluctuations.

Greece joined soon after, in 2001. When euro coins and banknotes were introduced in January 2002, it was one of the largest financial transitions in modern times. ATMs were updated overnight, shop prices adjusted, and millions of people started using the new currency almost immediately. In the years that followed, the euro area kept expanding — Slovenia joined in 2007, Malta and Cyprus in 2008, Slovakia in 2009, and, most recently, Croatia in 2023.

Former Currencies and Euro Adoption Timeline

| Country | Former Currency | Joined Eurozone | Euro Cash Introduced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Schilling | 1999 | 2002 |

| Belgium | Belgian Franc | 1999 | 2002 |

| Finland | Markka | 1999 | 2002 |

| France | Franc | 1999 | 2002 |

| Germany | Deutsche Mark | 1999 | 2002 |

| Ireland | Irish Pound | 1999 | 2002 |

| Italy | Lira | 1999 | 2002 |

| Luxembourg | Luxembourg Franc | 1999 | 2002 |

| Netherlands | Guilder | 1999 | 2002 |

| Portugal | Escudo | 1999 | 2002 |

| Spain | Peseta | 1999 | 2002 |

| Greece | Drachma | 2001 | 2002 |

| Slovenia | Tolar | 2007 | 2007 |

| Cyprus | Cypriot Pound | 2008 | 2008 |

| Malta | Maltese Lira | 2008 | 2008 |

| Slovakia | Slovak Koruna | 2009 | 2009 |

| Estonia | Kroon | 2011 | 2011 |

| Latvia | Lats | 2014 | 2014 |

| Lithuania | Litas | 2015 | 2015 |

| Croatia | Kuna | 2023 | 2023 |

The European Central Bank has noted that the euro made trade simpler, encouraged price transparency, and lowered the cost of exchanging money (ECB). But the single currency also brought challenges. Countries that joined gave up certain tools for managing their own economies, such as the power to adjust interest rates or devalue their currency in hard times. When the global financial crisis hit in 2008, the loss of flexibility made recovery more difficult for several members.

Even with those difficulties, the euro soon became part of daily life. Today it’s used by more than 340 million people across 20 countries, and several nations outside the EU keep it in their reserves. What began as a daring political idea has grown into one of the world’s most stable and widely trusted currencies — a lasting example of how much Europe has accomplished together.