Dutch land reclamation efforts

The Netherlands has a coastline continually transforming with erosion induced by water and wind. The Dutch people populating the region had constructed primitive dams to defend their settlements from the sea.

In the northern territories of the Netherlands, sea levels dropped, uncovering new land at a rate of 5–10 meters per year between 500 BC and 500 AD. Dutches used this natural process to get new agricultural lands, protecting new farms by discontinuous dams.

Land reclamation in the Netherlands has a rich history. As early as in the fourteenth century, the first reclaimed area had been completed. More petite strips of land were reclaimed by filling them with sand or other ground materials. It was usually done close to the cities and harbor areas.

The effect of operating windmills for pumping water in the 15th century let the draining of substantial bodies of water.

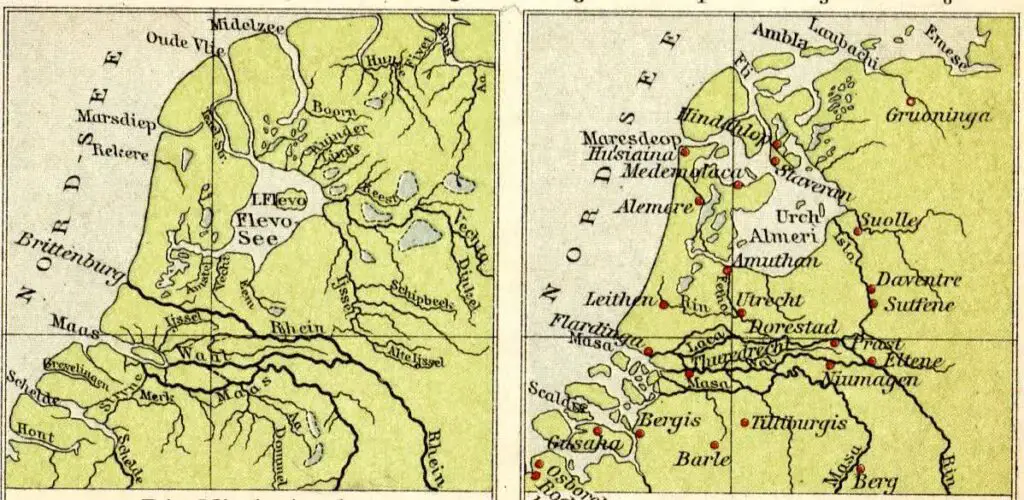

Below are the maps of the Netherlands between the 1st Century AD (left) and 10th Century AD (right), showing the effect of the constantly sinking coastline.

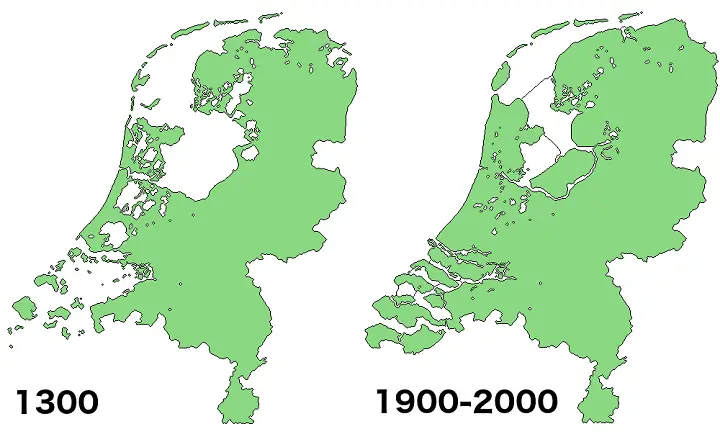

In the 13th century, the Dutch began developing methods and technologies to deal with flooding. The map below created by K. Cantner shows how the territory of the Netherlands has changed after applying these methods.

Many of the current land reclamations have been done as a part of the Zuiderzee Works after 1918.

The Netherlands is often associated with polders – a low-lying parcel of land that creates an artificial hydrological entity encompassed by a barrier. Nowadays, the Netherlands has about three thousand polders. Approximately 50% of the entire surface area of polders in northwest Europe locates in the Netherlands.

The map below shows the main stages of land reclamation in the Netherlands since 1300.

By 1961 6.8 thousand square miles (18 thousand km2), nearly half of the nation’s territory, was reclaimed from the sea.

As of 2017, about 17 percent of the total land area of the Netherlands has been reclaimed from the sea. As a result, approximately 65 percent of the nation would be underwater at high tide without dams and pumps. Land reclamation in the 20th century added 1,650 sq km or 640 sq mi to the nation’s land area. Today 21 percent of the Netherlands ‘ population dwells in 26 percent of the land below mean sea level.

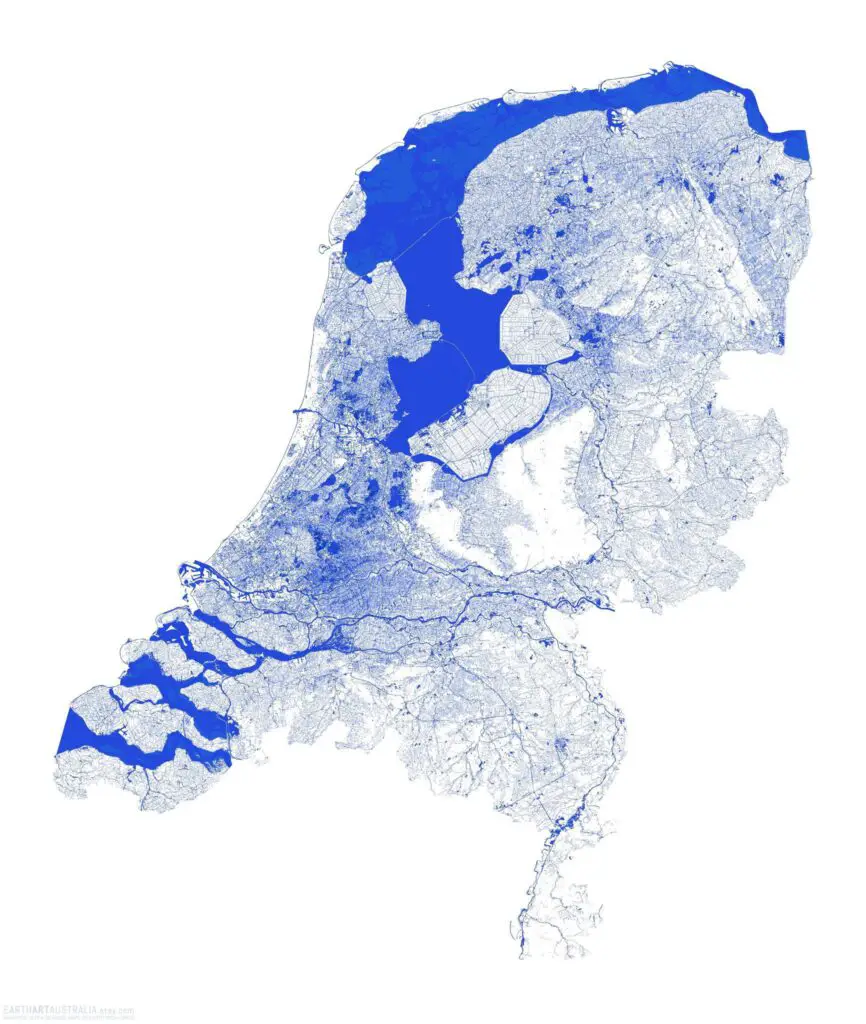

The map below shows how much of the Netherlands is below sea level.

But this is not the only problem in the Netherlands. There are many rivers in the country. The map below shows all waterways of the Netherlands.

The rivers discharge by gravitation at low tide. At high tide, the water level in the rivers rises due to a decrease in discharge. The water level at the river estuaries is at sea level. The waterways below sea level are the large drainage systems that are only joined with the main rivers with inlets, locks, and pumping stations. Large pumping stations (like the one in Katwijk) have a pumping capability that is high enough to drain the inland waterways called “boezem” to the wanted water level (at Katwijk about -0.61 meters below mean sea level). The deep polders (at about 5 meters below mean sea level) discharge water from those territories on the “boezem” with smaller pumping stations.

Pumps, for example, every raindrop that falls in Flevoland (the sizeable human-made island in the heart of the Netherlands), have to be pumped out.

Approximate numbers: 750mm of rain, of which 500mm evaporates, that’s 250mm of pumping, or 250 liters/ m2, or 250.000 m3 / km2, Flevopolder is 970 square km, so each year 240 million cubic meters of water needs to be pumped out.

About all water that drops below sea level is pumped out, it often pumped to river/canals, which flow directly to the sea, but all of it is first pumped up.

Forth percent of the Netherlands is below sea level, so that would be 13600 km2 and 3,4 billion cubic meters of water every year. The Rhine runs with 2330 m3/sec, so it needs to flow 17 days to get 3,4 billion km3 of water (the Mississippi needs to flow 56 hours while the amazon can do it in under 5 hours).

Related post:

– Land Reclamation in Monaco (1861 – 2024)

At the end of the last ice age, Britain formed the northwest corner of an icy continent. Warming climate exposed a vast continental shelf for humans to inhabit. Further warming and rising seas gradually flooded low-lying lands. Some 8,200 years ago, a catastrophic release of water from a North American glacial lake and a tsunami from a submarine landslide off Norway inundated whatever remained of Doggerland.

https://www.nationalgeographic.org/maps/doggerland/

Any reason they aren’t trying to expand further?

Some guesses:

-A lack of shallow water

-Environmental impact concerns

-No longer economically viable to maintain

-Less demand for rural land

-Worries about sea level rise in the future