The Changing Shoreline of New York City

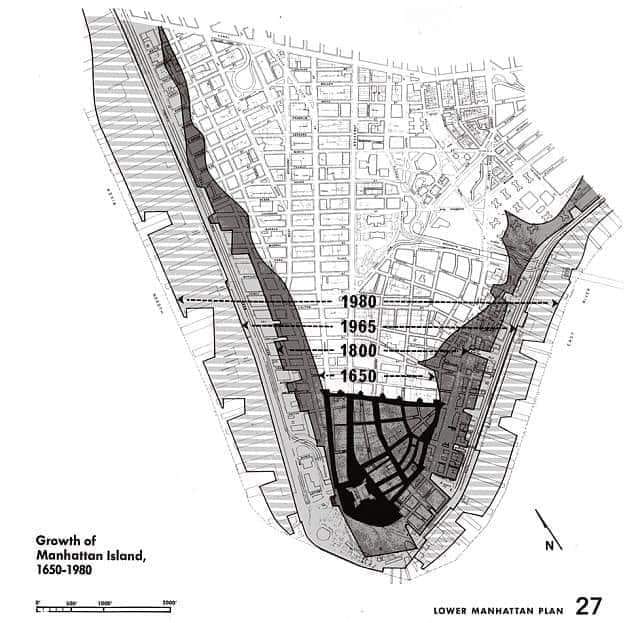

Walk around the southern tip of Manhattan and you might not realize you’re standing on ground that wasn’t there when the Dutch showed up. Below City Hall, the island is half again as big as it was in the 1620s. Those streets near the water? The small parks where people grab lunch? Entire blocks of apartments? All of it used to be river and marsh. Over the centuries, New Yorkers kept adding fill and pushing the edge outward. The island today looks completely different from what Europeans found when they first sailed in.

When Water Became Land

The Dutch arrived in 1626 and began draining the wetlands that surrounded their new settlement. They dug a canal that ran inland from the water at today’s Broad Street and built up the edges along the coast. The goal wasn’t really to gain extra land. They wanted to make the place healthier because people thought wetlands caused diseases. Plus, the Dutch liked practical solutions, and a canal meant boats could sail directly into town.

They called it Heere Gracht—“Gentleman’s Canal.” It started at Pearl Street and ran down to Beaver Street, following what later became Broad Street. By the 1640s, three-story houses lined both banks of this canal, with wooden bridges connecting the two sides. The problem? Everyone treated it like an open sewer. When the English took over in 1664, the canal was so disgusting they filled it in. That was around 1676.

Selling the Shoreline

The English figured out how to make money off the tides. Colonial officials started selling what they called water lots—strips of shoreline that were underwater at high tide but exposed when the tide went out. The Dongan Charter in 1680 authorized these sales. Then in 1731, the Montgomerie Charter let buyers claim lots twice as far out, going from 200 feet to 400 feet into the East River.

If you bought a water lot, you’d head down to the shore at low tide and build a retaining wall. Then you’d spend months or years filling in everything behind that wall with whatever you could find. This solved a real problem for merchants. Instead of anchoring in deep water and moving cargo to smaller boats, ships could pull right up to the wharves. It was faster and cheaper. By the time the Revolution started, British New York had added something like five hundred acres to Lower Manhattan this way. The historian Ann Buttenwieser described what went into all that fill: “Ballast was dumped and ships sunk, hills leveled, building sites and roadways excavated, wastes, ashes and sweepings collected, and all were deposited at the water’s edge.”

Building on Fill

The Battery is right at the tip of Manhattan now. In 1808, though, it sat on its own island three hundred feet offshore. Workers started construction on a circular fort that year, connecting it to Manhattan with a wooden causeway and drawbridge. The War of 1812 came and went without the fort seeing any action. Afterwards, they renamed it Castle Clinton.

The city began dumping fill around Castle Clinton in 1855, using dirt excavated from various street-widening projects around Manhattan. Gradually, the water that separated the fort from the rest of the island filled in. Eventually Castle Clinton sat on dry land, connected to everything else. From 1855 to 1890, it processed immigrants—7.5 million people passed through before Ellis Island opened and took over the job.

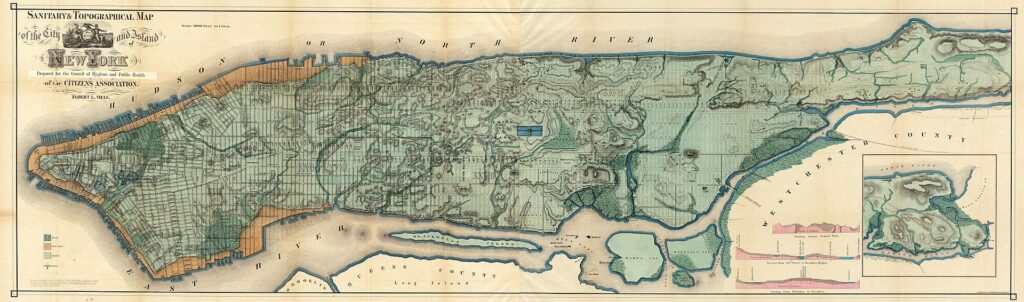

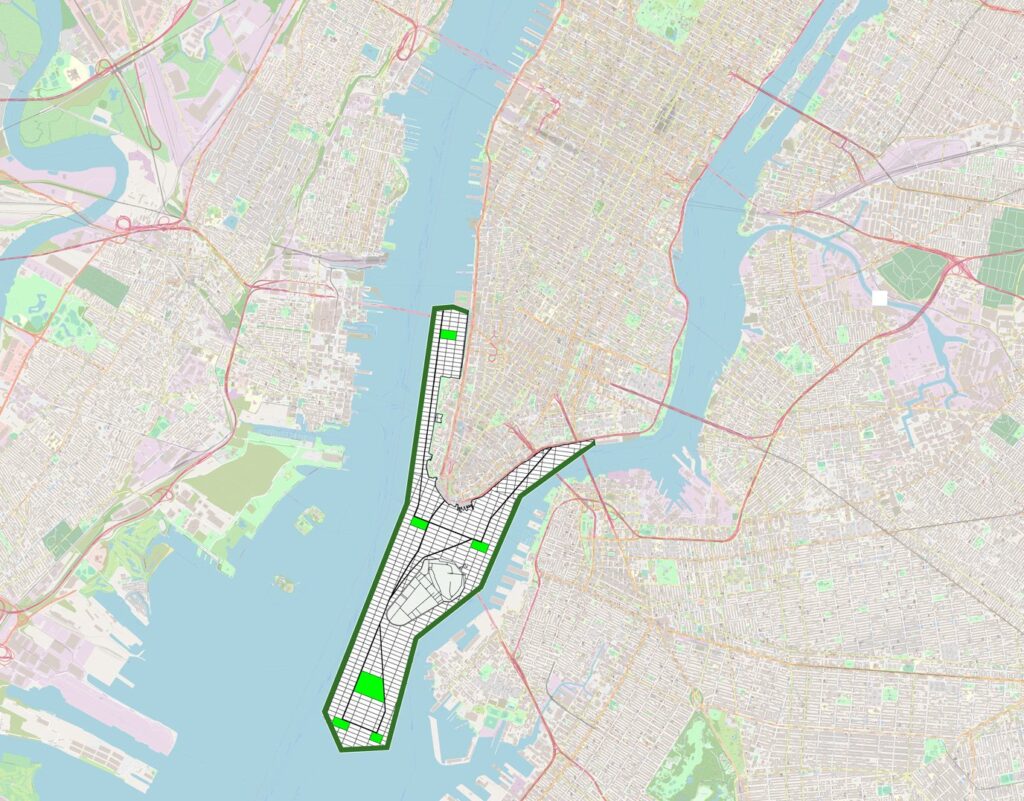

Below is Egbert Viele’s 1865 topographical map showing the extent of landfill in Manhattan to that point.

By the 1970s, somewhere between 1,400 and 3,000 acres of Manhattan was sitting on fill. Some estimates put it at 29% of the whole island.

The Biggest Earth-Moving Project

The World Trade Center project reshaped more waterfront than anything in the city’s history. The site was already built on old fill. To reach bedrock for the tower foundations, crews had to dig down 65 to 70 feet. All that digging produced 1.2 million cubic yards of material. Rather than pay to truck everything to landfills across the river in New Jersey, city planners had another idea: why not dump it in the Hudson and create new land?

New York State set up the Battery Park City Authority in 1968 to turn 92 acres of river into a neighborhood. The Trade Center excavation supplied roughly a quarter of the fill. Dredging operations in the harbor provided the rest. Trucks spent years moving material across West Street. Battery Park City now has 9,300 residents spread across 30 towers, plus office space, parks, a marina, and the waterfront esplanade that runs along the Hudson.

Waterside Plaza at 25th Street took things even further. The 1973 development sits on platforms that jut out over the East River. Engineers sank more than 2,000 steel piles eighty feet into the riverbed to support everything. Four towers contain 1,470 apartments. Nobody else in Manhattan lives this far east—it’s the only residential complex that sits on the far side of the FDR Drive.

The Plans That Never Happened

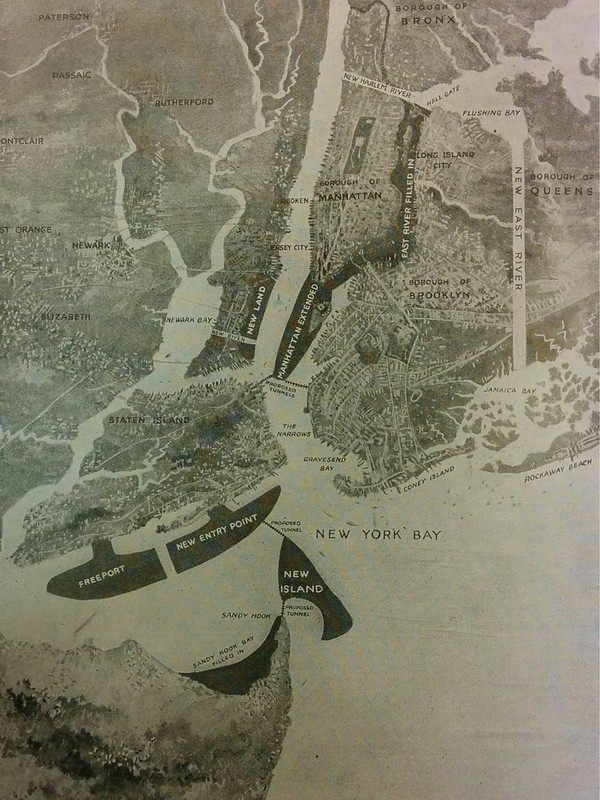

Not every idea made it off the drawing board. T. Kennard Thomson was an engineer who spent decades promoting what might be the most audacious proposal in New York history. His 1911 plan called for damming the entire East River and filling it in. Manhattan and Brooklyn would extend four miles into the harbor. Staten Island would get new peninsulas. A canal carved from Long Island Sound to Jamaica Bay would give the city a completely new port.

Thomson calculated this “Really Greater New York” would add fifty square miles.

A decade passed before the New York Times wrote about a scaled-back version that only extended Manhattan four miles into the harbor. The paper assembled lawyers, planners, and engineers to weigh in. Nobody saw any real legal or engineering problems with it. Thomson worked on variations of his expansion ideas until 1952, when he died. He’d been going to his office near Bryant Park almost daily, still trying to convince people.

John A. Harris tried something similar in 1924. His scheme involved damming the East River, filling in the riverbed, and constructing a huge civic center and arts complex on top.

The conversation about extending the shoreline hasn’t stopped. The difference now is why people want to do it. Instead of gaining land for development, recent proposals emphasize flood protection and climate adaptation.

In 2022, Rutgers University urban economist Jason Barr proposed expanding Lower Manhattan. His plan, called ‘New Mannahatta,’ would create 1,760 acres of reclaimed land at the tip of Manhattan to provide housing and help combat climate change.

Manhattan’s shoreline reads like an archaeological palimpsest: each line of fill, each reclaimed block, tells a different chapter of the city’s ambitions — defensive works and wharves, profit-driven land sales, massive 20th-century engineering, and, most recently, climate-adaptation thinking. What looks fixed on a modern map is often the product of deliberate human labor and shifting priorities. As you compare the 1660 outline with later proposals like the 1911 expansion plan, the constant becomes clear: New York has always remade its edges to meet new needs. Which raises a question for our century — will future generations redraw these same lines again, this time in the name of resilience?