America’s great housing divide: Are you a winner or loser?

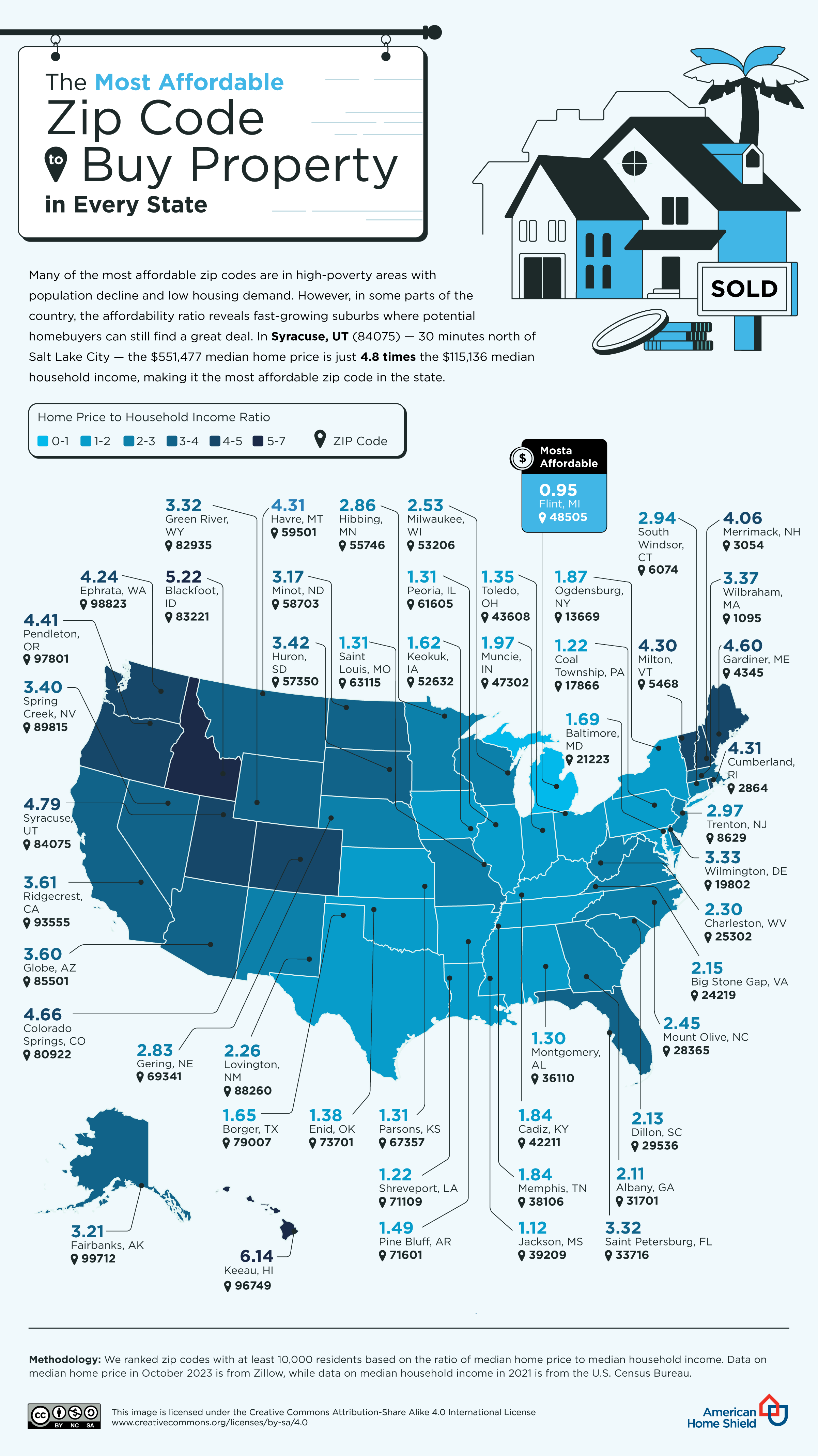

The Post analysis, based on data from Black Knight Financial Services spanning 2004 through 2015, shows how the nation’s housing recovery has exacerbated inequality, leaving behind many Americans of moderate means. It also helps explain why the economic recovery feels incomplete, especially in neighborhoods where the value of housing – often the biggest family asset – has recovered little, if at all.

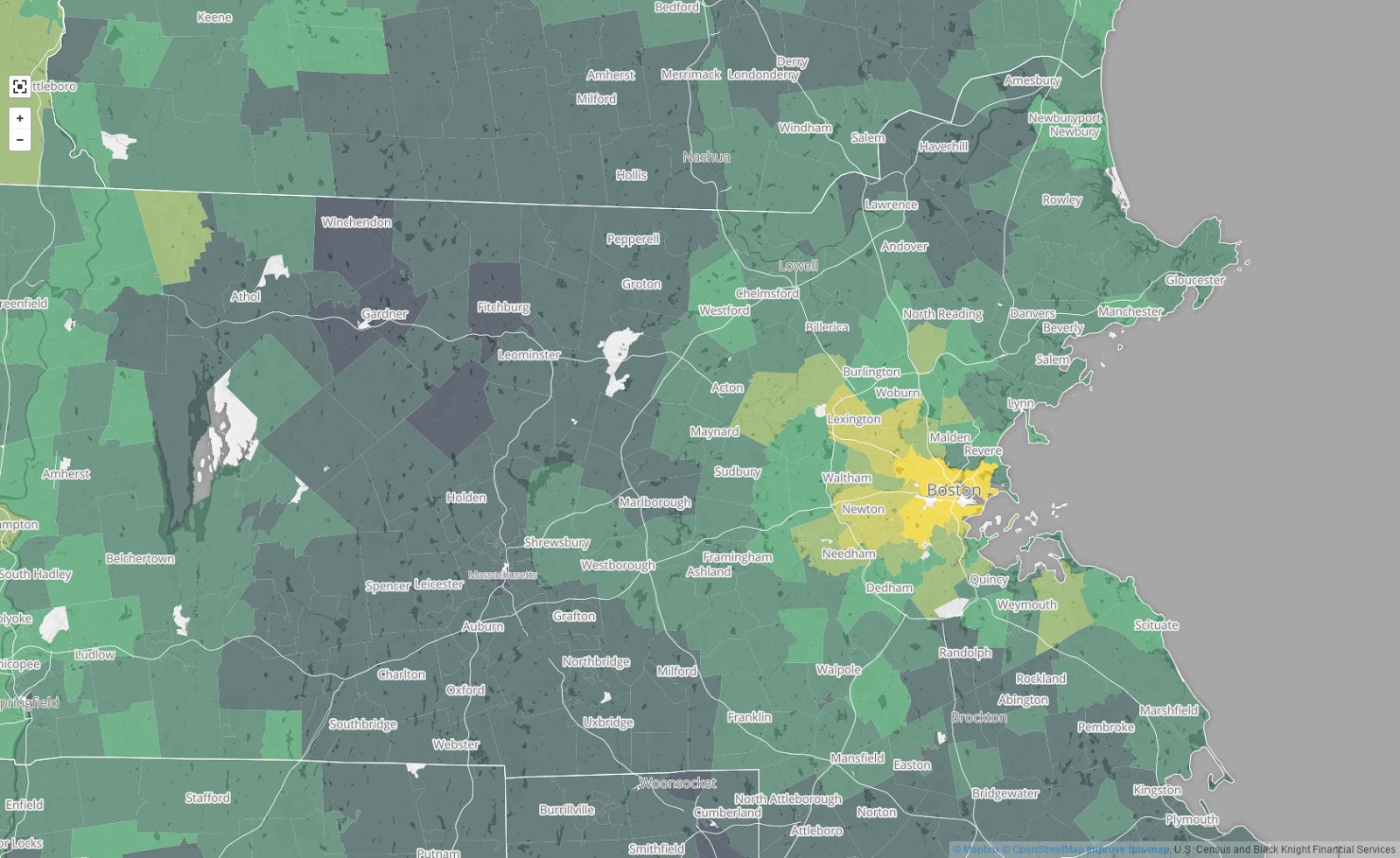

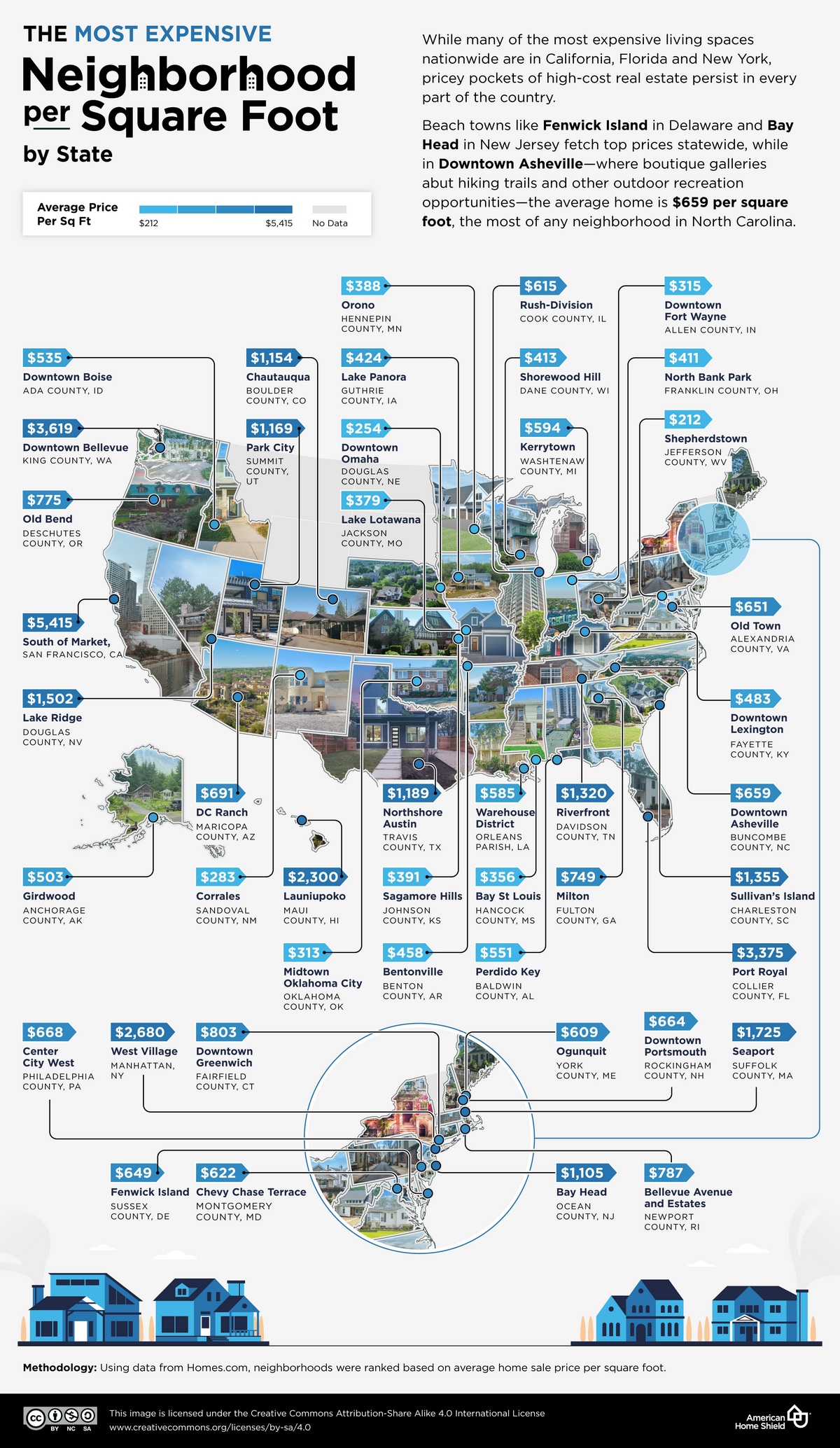

While a typical single-family home has gained less than 14 percent in value since 2004, homes in the most expensive neighborhoods have gained 21 percent. Regional factors such as the Western energy boom explain some differences, but in many cities the housing market’s arc has deepened disparities between the rich and everyone else, such as in Boston, where gentrifying urban neighborhoods have thrived and far-flung suburbs have fallen behind.

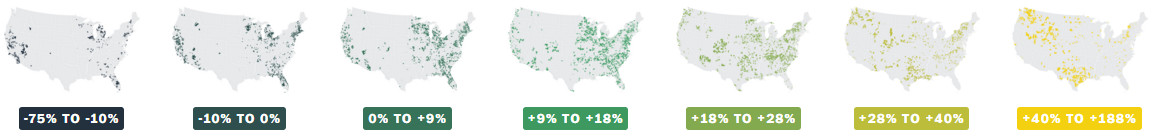

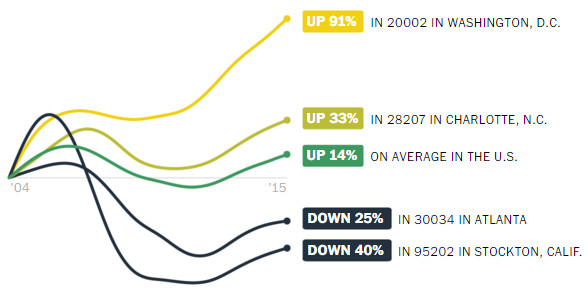

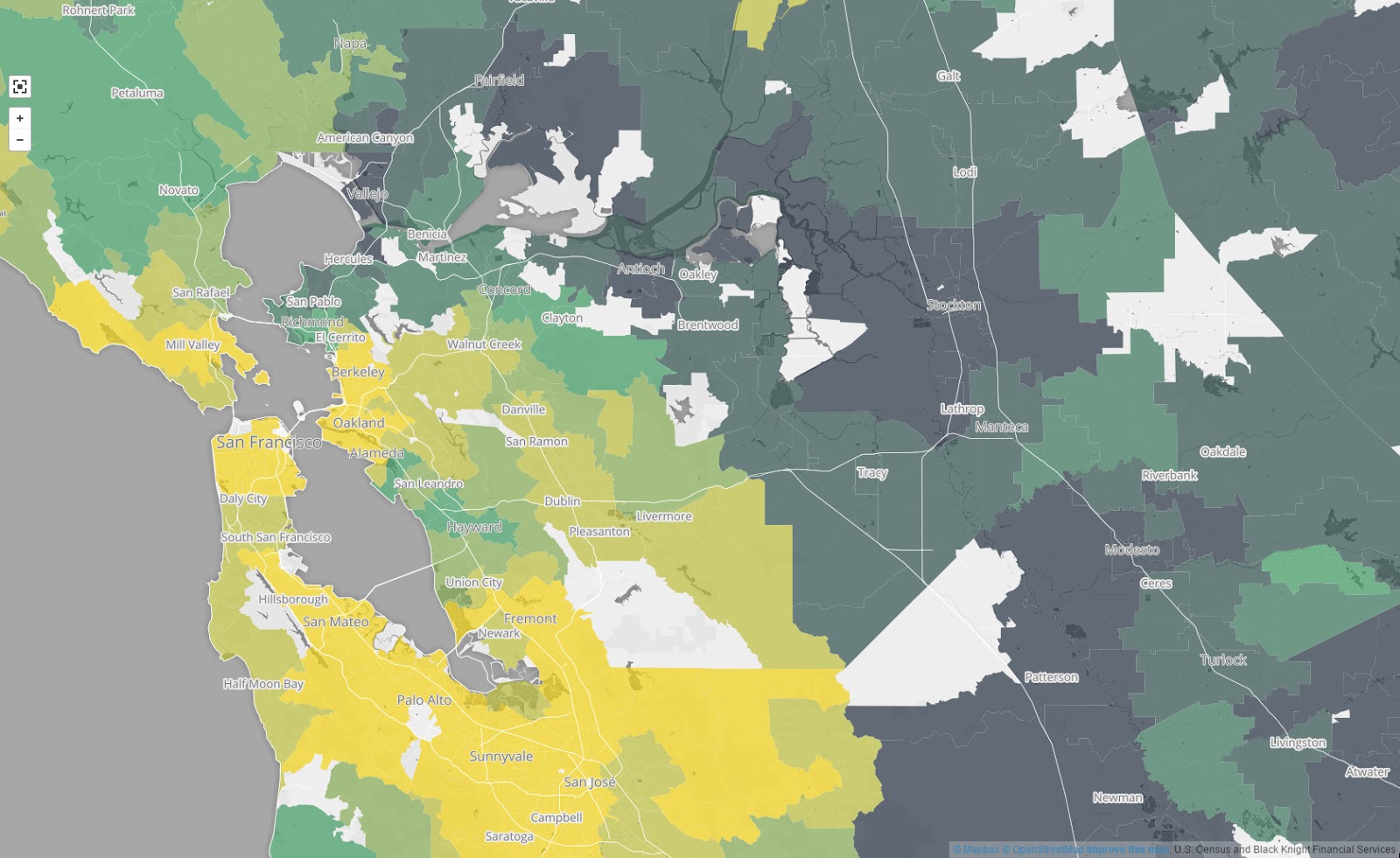

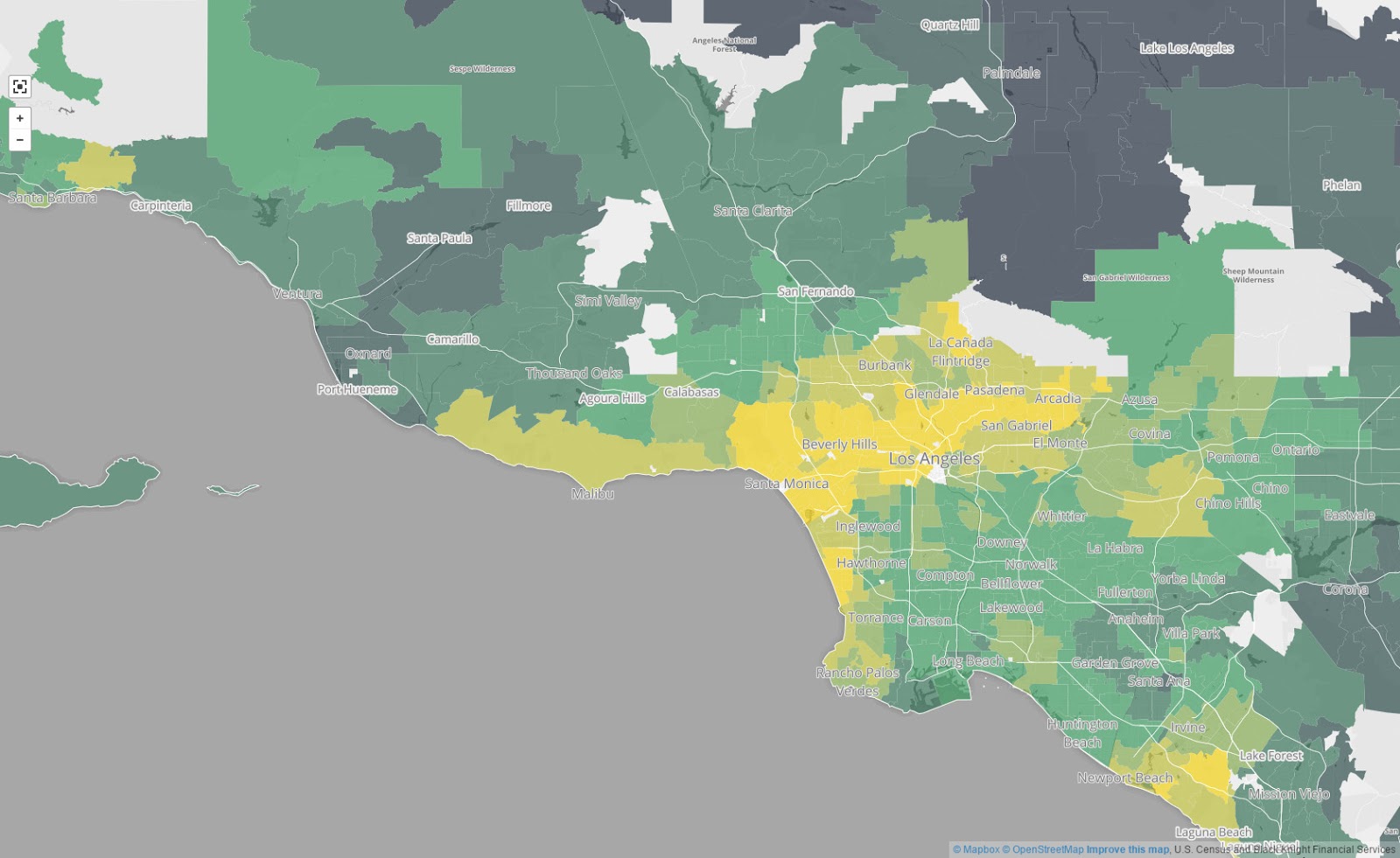

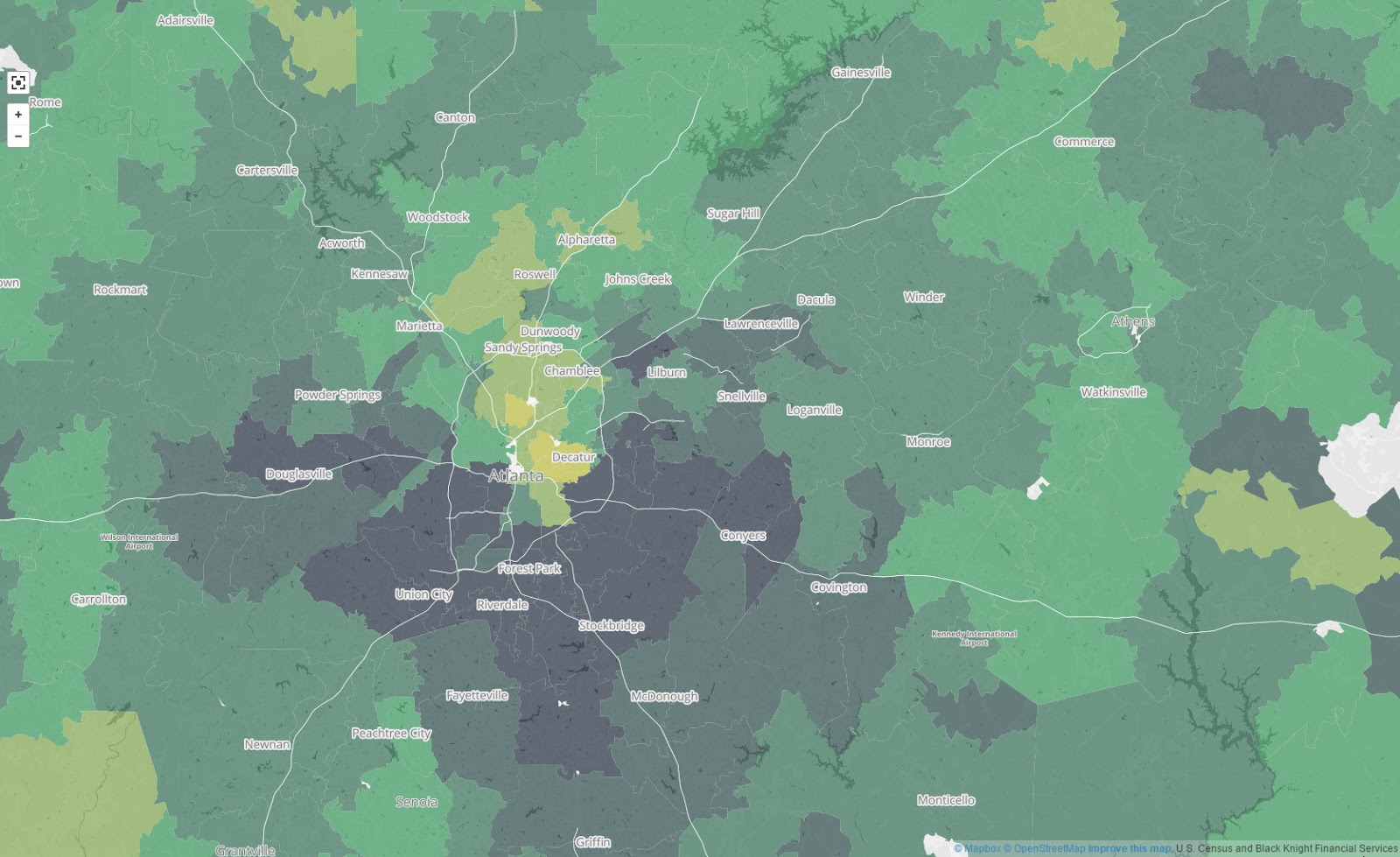

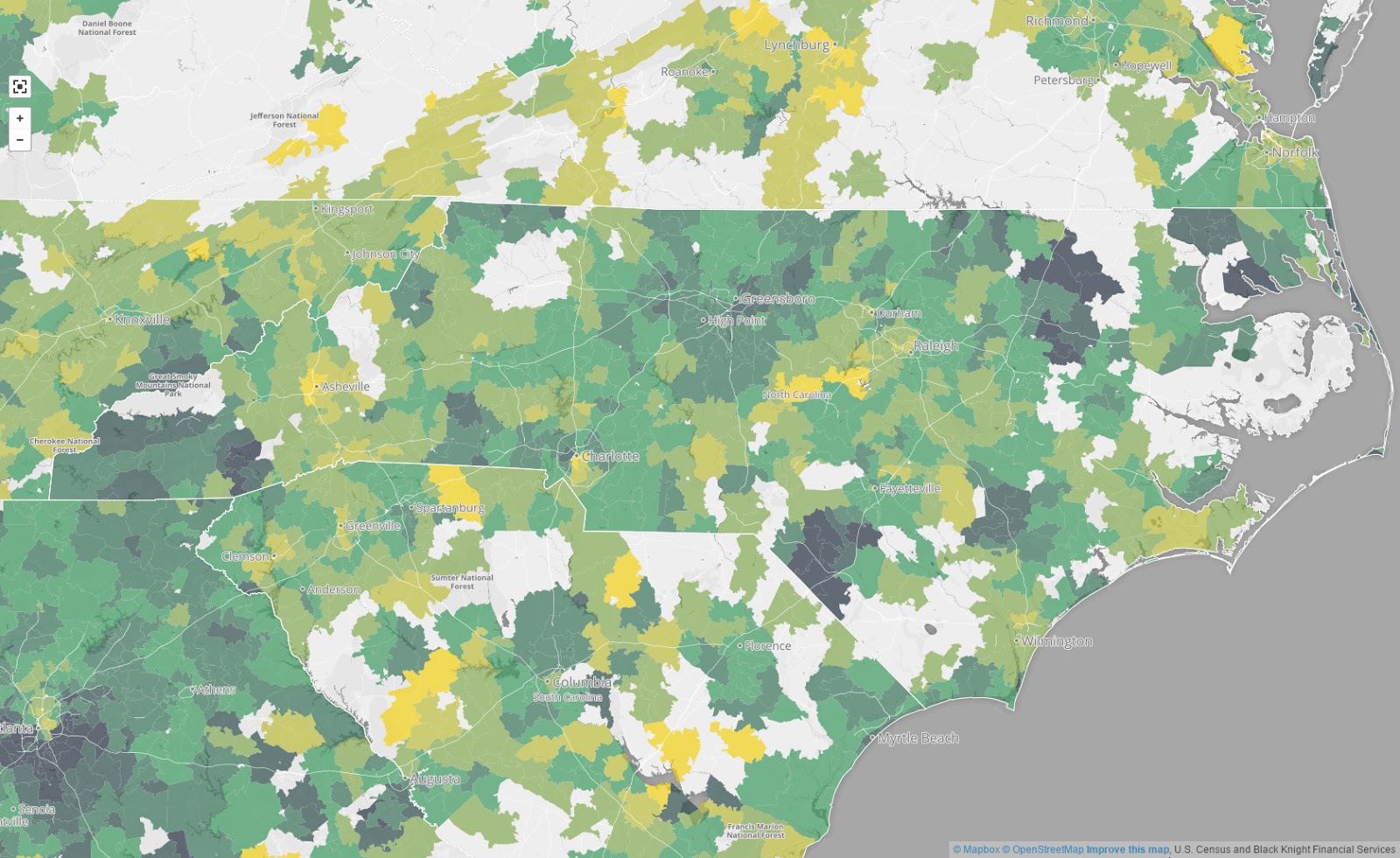

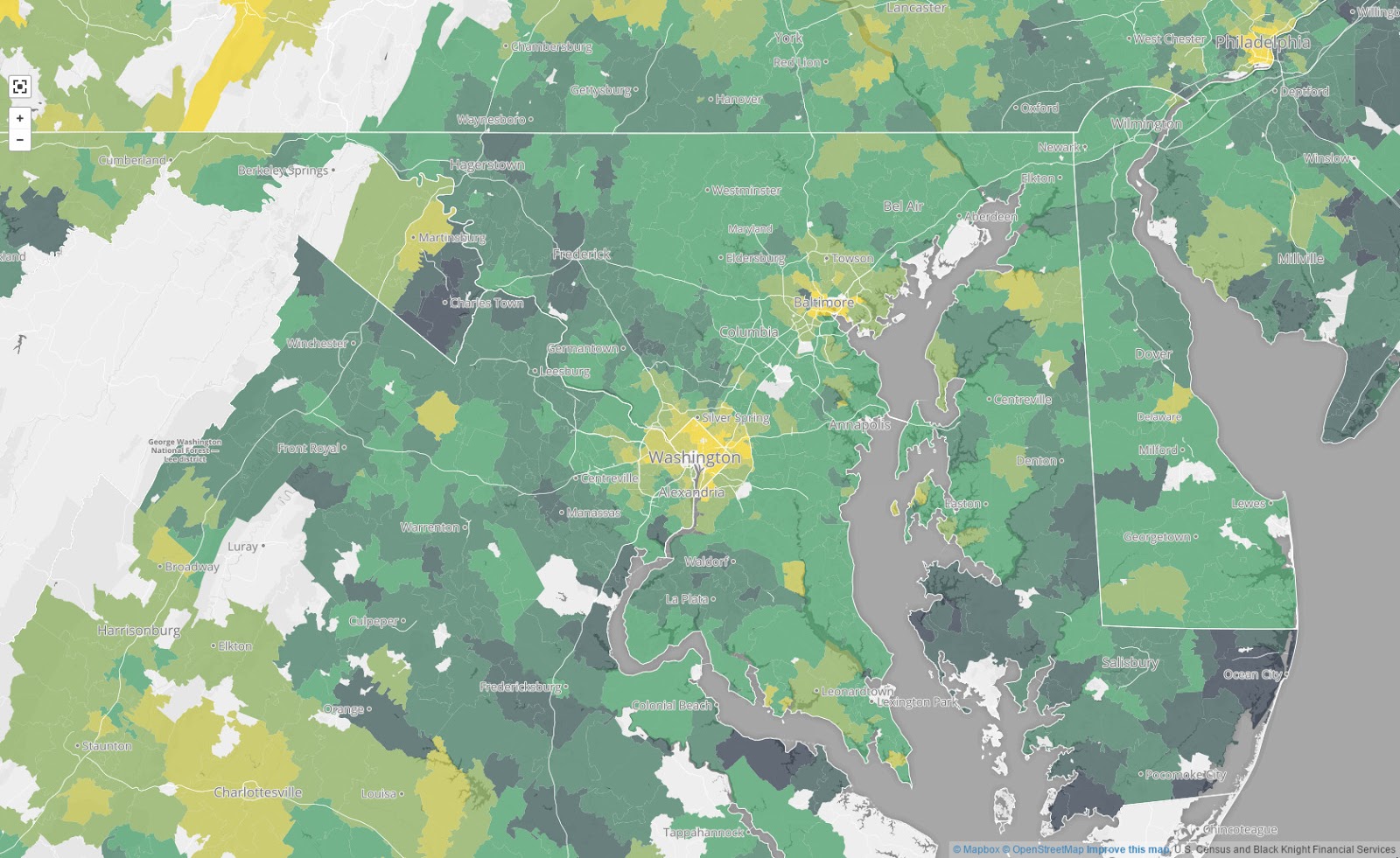

These maps and the stories that follow are built upon an analysis of how home values have changed since near the start of the nation’s housing turmoil in 2004 in 19,000 Zip codes. They show where housing values have enjoyed the best growth, and where they’ve suffered most.

At the beginning of this period, values escalated rapidly in the bubble, fueled by financial speculation, subprime lending and an abiding national faith in homeownership as a sure-fire source of wealth. Prices peaked by 2007, then collapsed, causing the worst recession since the Great Depression. Trillions of dollars of wealth were lost and millions lost their homes to foreclosure as values dropped to their nadir in 2011. Since then, the recovery has been swift for some and sluggish for others, creating a fractured national map of housing fortunes.

The findings of The Post’s analysis underscore another way in which the economy, despite its improvements over the past several years, continues to deliver better returns for some Americans than others.

In good times, housing converts income into wealth. It turns a paycheck into the next generation’s inheritance. But in neighborhoods that haven’t weathered the past decade as well, homes have become a source of debt, a physical trap and an obstacle to life’s other goals.

Among major cities, home values are up the most in a broad band from Texas up to the Northwest. Metro areas that are still feeling the most pain – where a dramatic housing bubble was followed by a dramatic plunge – are in California’s Central Valley, the upper Midwest, the suburban Northeast and, of course, Florida.

As dizzying swings in home values have settled, it’s now possible to take stock of these differences and where we stand after a uniquely tumultuous time in American housing.

“Things have been calm enough for long enough that we have some clarity,” says Jed Kolko, a senior fellow at the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California at Berkeley. “U.S. housing markets are more unequal today than they were before the housing bubble. The spread in home values has gotten bigger. The spread in incomes has gotten bigger. America’s cities today are less like each other on these measures than they were before the bubble.”

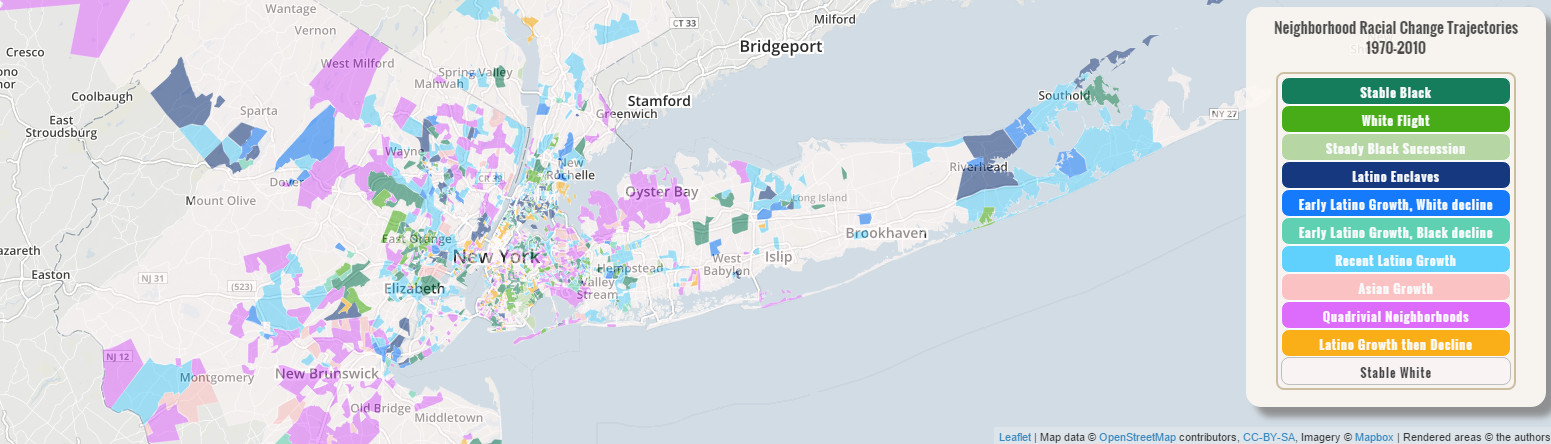

The Atlanta metro Zip codes where home values have fallen the farthest — and where they remain low — are predominantly African American, widening housing inequality along racial lines. South DeKalb County on the city’s eastern edge is home to many African American professionals who bought stately new suburban homes during the boom. But they have been left out of the recovery.

In Mecklenburg County, as in the nation as a whole, housing values have gained the most in neighborhoods that already had the most expensive homes, widening the wealth advantage of upper-income households. The few exceptions are often neighborhoods undergoing fundamental changes through gentrification.

In the heart of the D.C., where home values are up more than 90 percent, a modest rowhouse in gentrifying Trinidad is now worth about as much as a newer, spacious suburban home in Loudoun County, where values have barely budged. Around Washington, the housing market’s winners and losers are divided by the Beltway. Inner-ring suburbs have outperformed outer-ring ones. That gives the best returns to short-commute neighborhoods once avoided for their schools, crime and poverty.

Many of the disparities reflect existing divisions in America that have been widened by the housing turmoil. The bubble was a broadly shared experience – values rose rapidly in communities across the country in the early 2000s -but what happened next was not. The bust was more severe in Stockton than San Francisco. The recovery was stronger in the District of Columbia than its suburbs. The pain of the bubble has lingered longer in African American neighborhoods of metro Atlanta than white neighborhoods. The result is that this housing cycle – spanning the bubble, bust and recovery – has left vastly different marks on communities across the country. For some families and neighborhoods, the legacy will linger for years. For others, its memory has already faded.