Climate Zones of the British Isles

The British Isles get battered by Atlantic weather systems, which keeps them mild and damp year-round. Most of the region has oceanic climate (Cfb): temperatures stay moderate, rain falls in every month, summers never get too hot, winters never get brutal.

But head into the mountains and things change. The Pennines running down northern England get cool enough to qualify as Cfc (cool-summer oceanic). The Scottish Highlands go further: the Grampians have spots of Dfd (very cold winter continental) and even tiny patches of ET (tundra) on the highest summits. These are the only genuinely harsh climates in the British Isles (For the climate codes and what they mean, check my earlier post on global climate zones.).

At least for now. I created maps showing how these climate zones have changed since 1930 and where they’re projected to go by 2099, using high-resolution Köppen-Geiger data from Beck et al. (2023) at 1-kilometer resolution.

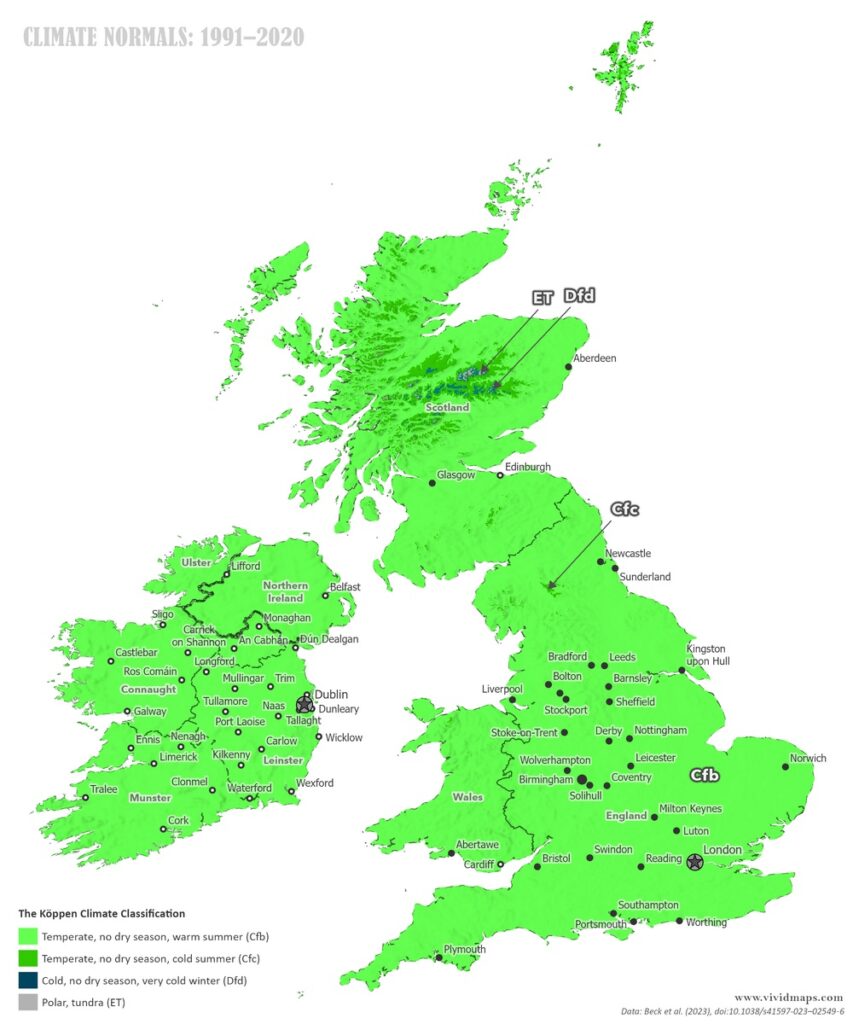

Today’s map shows what you’d expect: green across almost everything. That’s Cfb, the oceanic climate. Ireland is entirely Cfb, as it has been and will remain through the entire span of these projections. The maritime influence is too strong for anything else.

Britain shows the same pattern across most of its area. But zoom into the uplands and exceptions appear. The Pennines display Cfc on their highest ground. Head north to Scotland, and the Grampian Mountains hold small areas of Dfd and even tinier patches of ET. Elevation creates these zones. Walk up a Scottish mountain and you can pass through multiple climate types in a single afternoon. The highest peaks stay cold enough that only tundra plants can survive there.

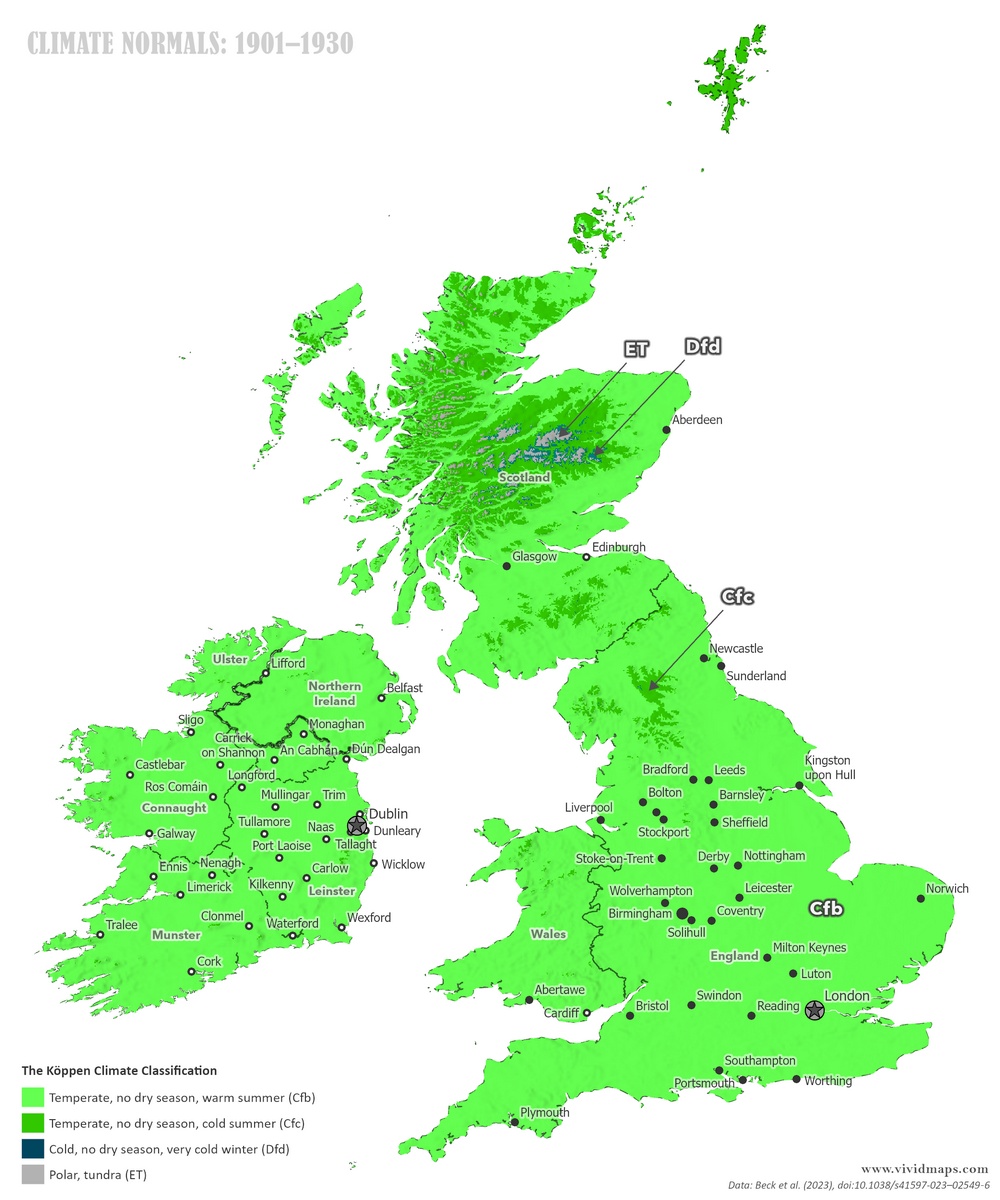

Changes Since 1930

Even in the relatively stable climate of the British Isles, a century of warming shows up.

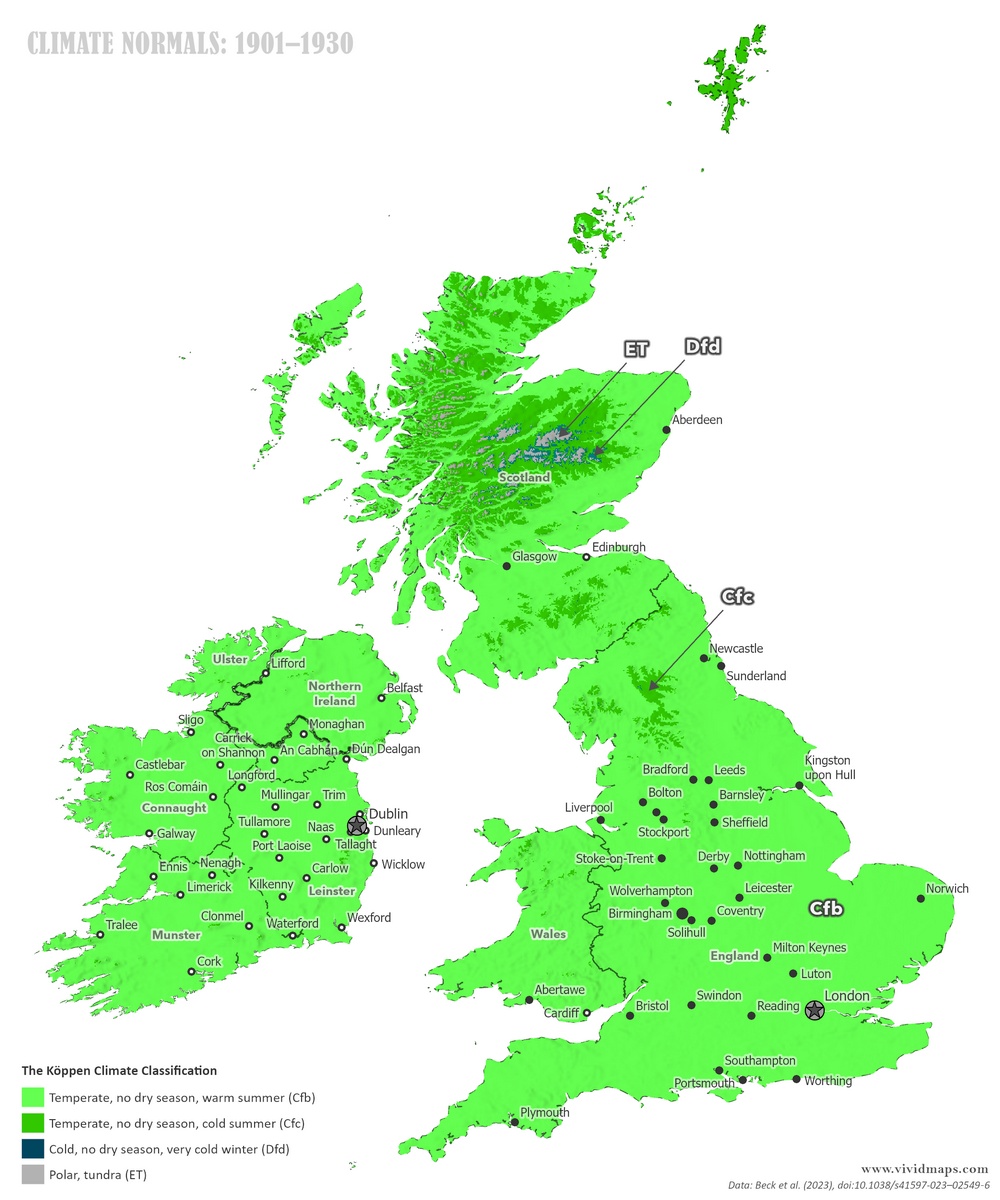

Early 20th century climate (1901–1930) versus modern climate (1991–2020).

The changes are subtle but measurable. The coldest zones in the Scottish Highlands have contracted. Areas that were Dfd or ET in 1930 have warmed enough to reclassify. The Pennines show similar but smaller changes. Across the lowlands, the shifts are minimal because the maritime influence dampens temperature swings. Ireland remains entirely Cfb.

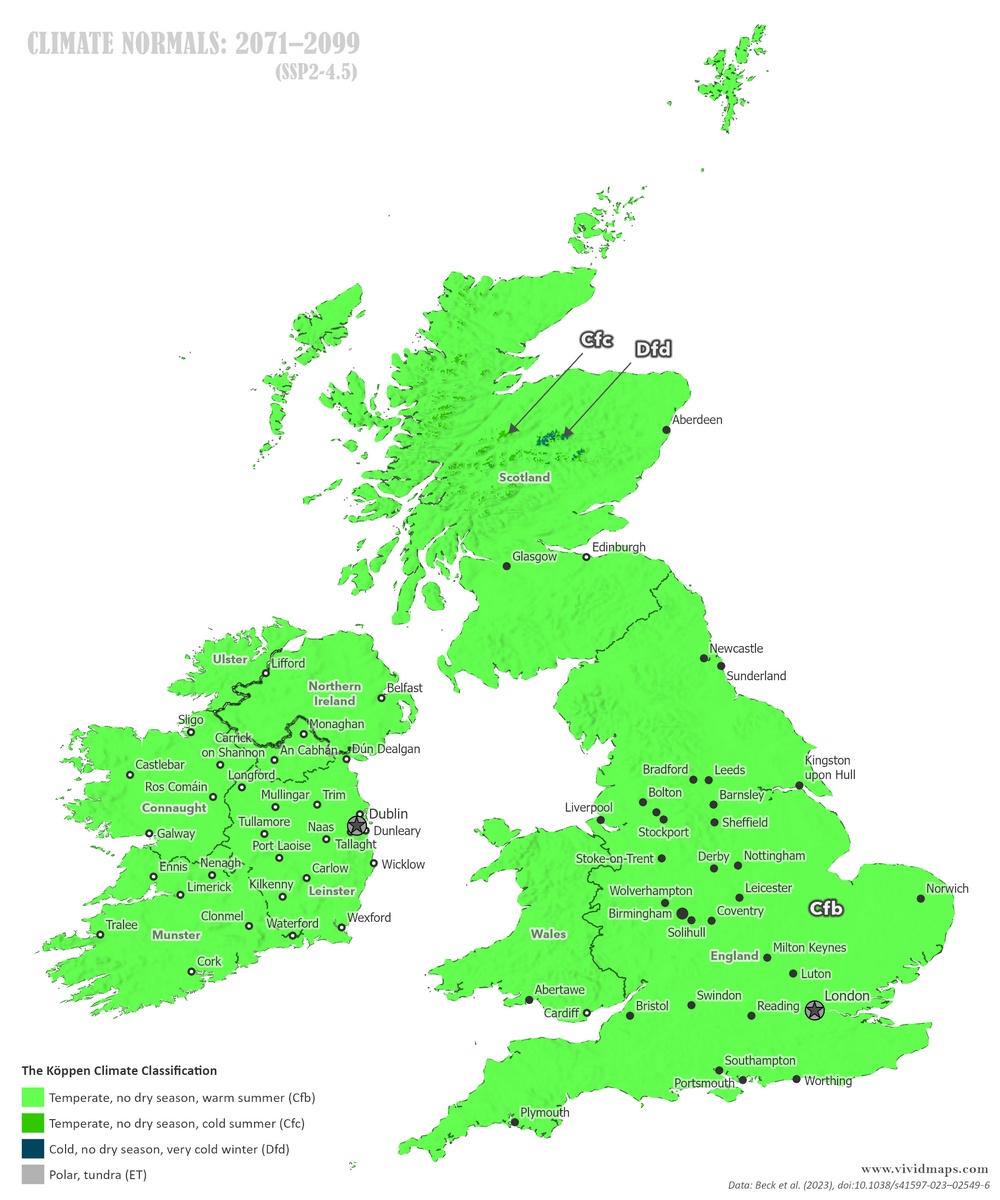

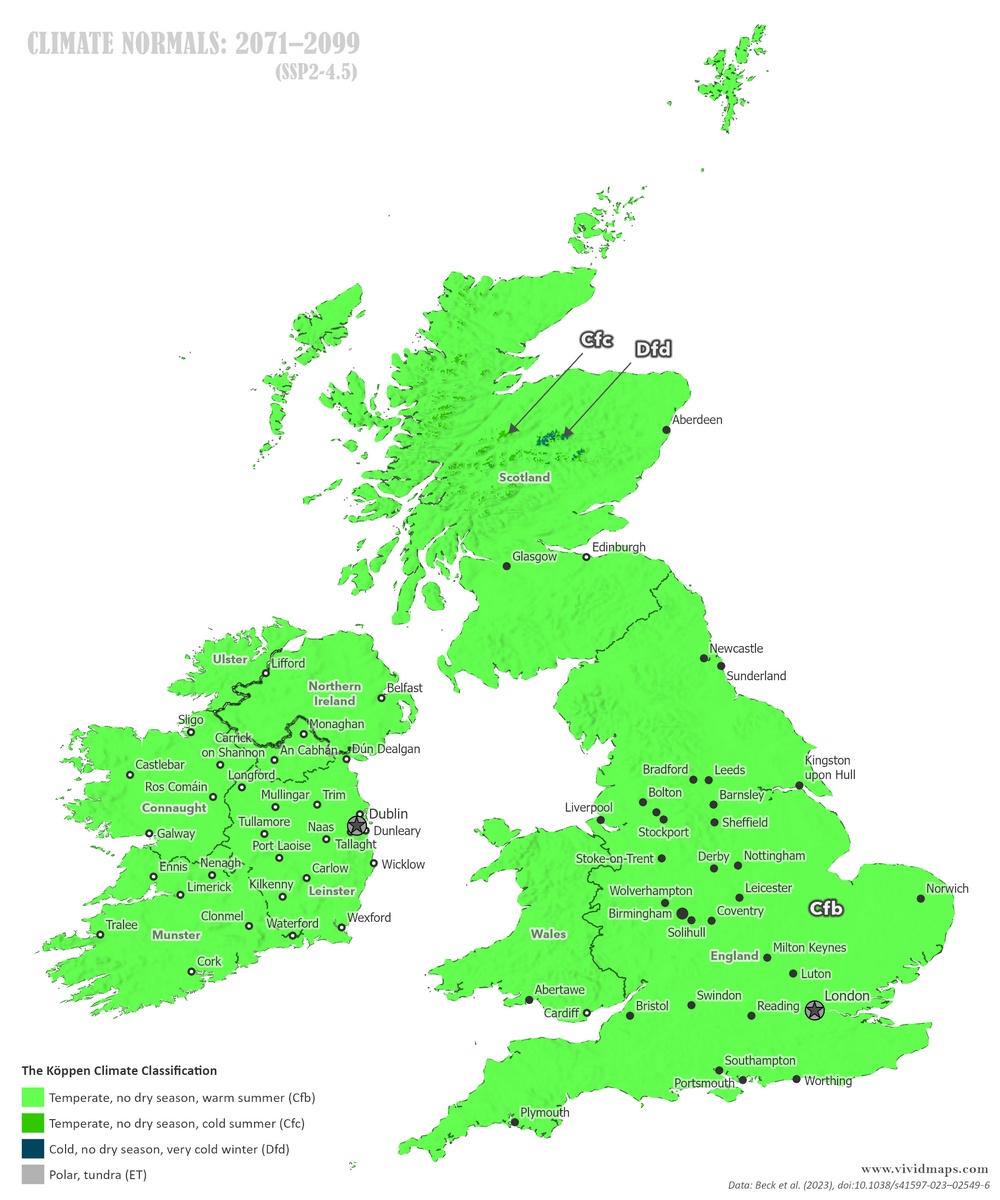

Projections to Century’s End

For future projections, I used the ssp2-4.5 scenario where emissions plateau by mid-to-late century.

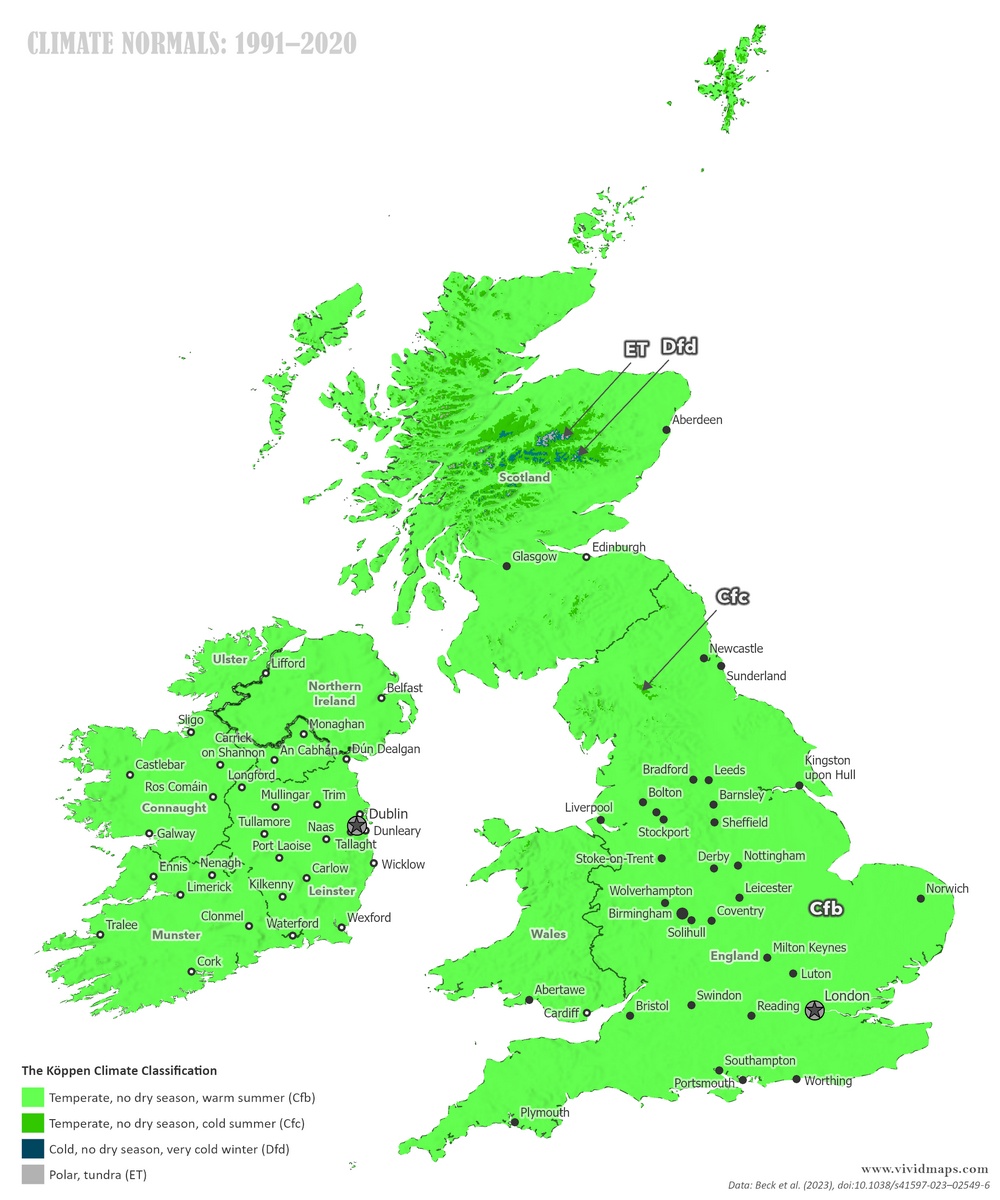

Current climate versus late-century projections (after 2077, ssp2-4.5).

By the 2070s, the Pennines lose their Cfc zones entirely. The whole range becomes Cfb. What counted as cool-summer oceanic crosses into warm-summer oceanic.

The Scottish Highlands change more dramatically. By the 2070s, the tundra patches (ET) disappear completely. The Grampians hold onto Dfd zones but lose their coldest characteristics. The highest peaks in the British Isles would no longer experience the extreme cold that defines their current ecology.

Over the full timespan, you watch the coldest zones retreat upslope and then vanish. In 1930, Scottish mountains held multiple climate zones stacked by elevation. By 2099, that diversity collapses.

Alpine and tundra plants that currently survive on Scottish summits are adapted to cold that will no longer exist. Species like mountain hare, ptarmigan, and dotterel depend on those conditions. Snow patches that persist through summer would melt earlier or disappear entirely. The mountains would look and function differently than they do now.

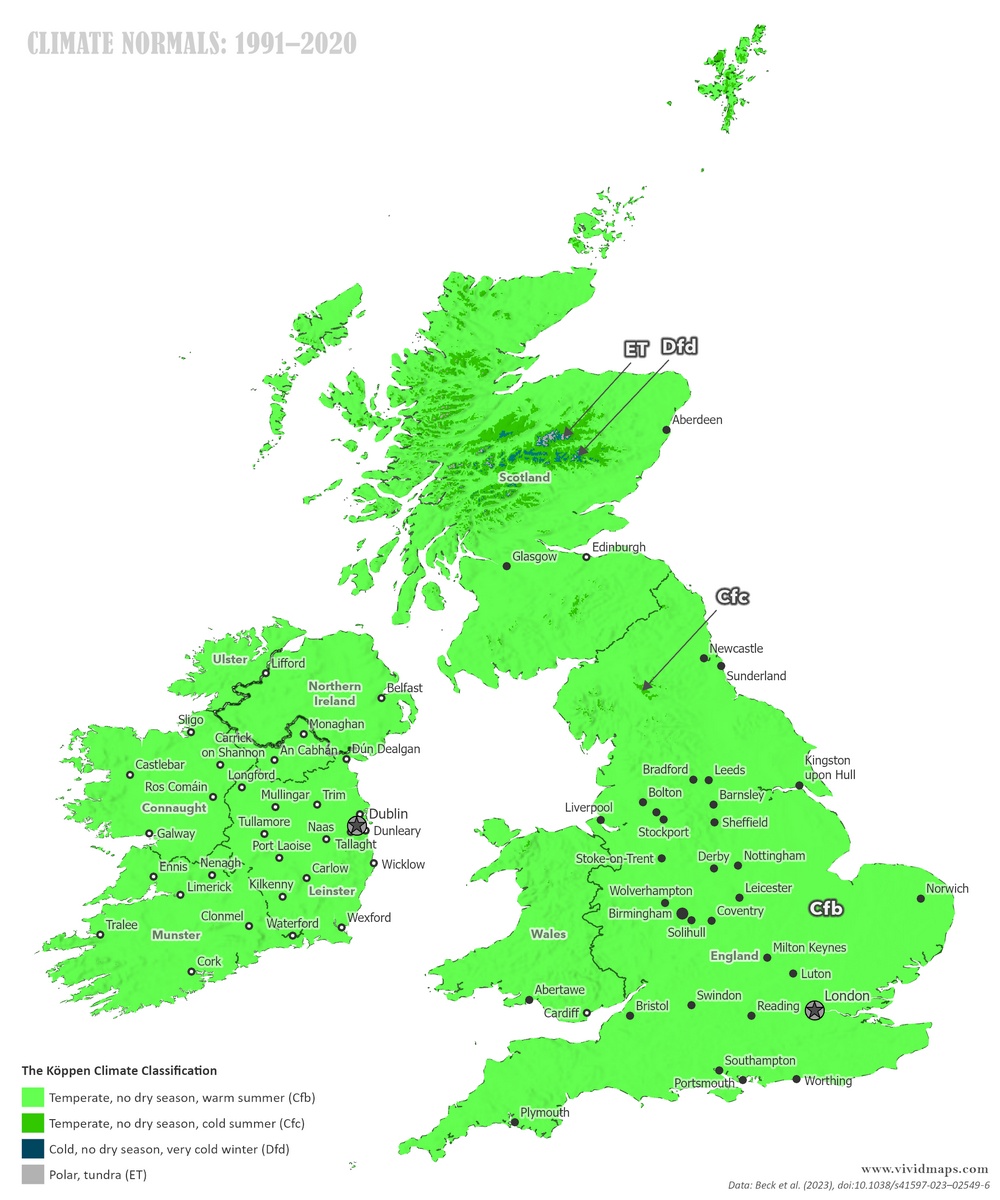

I also made maps for 1931–1960 and 2041–2070. The full animation:

British Isles climate zones from 1931–1960 through 2041–2070.

Ireland is not in the British Isles. Hasn’t been for ages.