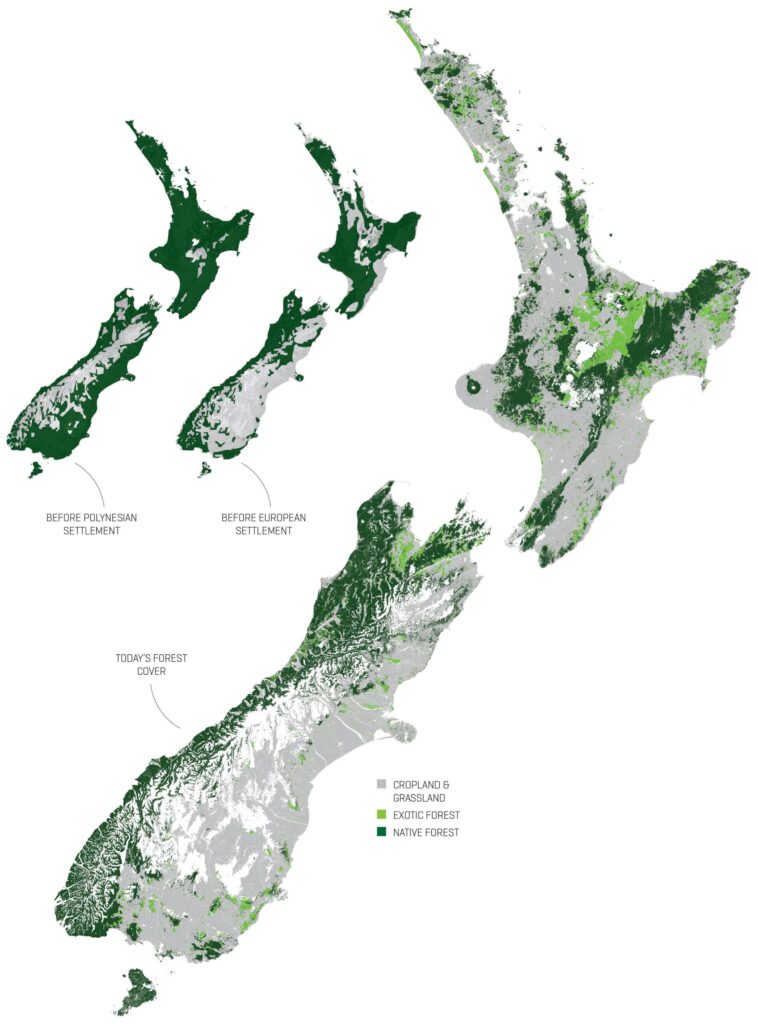

New Zealand’s Disappearing Forests—Mapped Through Time

New Zealand once had some of the most untouched forests on Earth. Before people set foot on the islands, forests covered more than 80% of the land. That changed quickly once humans—and fire—arrived.

The maps below show how forest cover changed over time.

When the first Polynesian settlers (Māori) arrived in the 13th century, they brought more than just canoes. They brought fire, dogs, and rats—tools and animals that reshaped the landscape quickly. Within just a couple of centuries, large stretches of forest were burned to create openings for travel, hunting, and the cultivation of kūmara and bracken fern. This wasn’t a gradual change. Pollen and charcoal records show a sharp drop in tree species and a surge in bracken, grasses, and ash around the mid-1200s.

By the time Europeans began settling in the early 1800s, much of the lowland forest was already gone. But colonization introduced new pressures: large-scale agriculture, logging of native timber species like rimu and tōtara, and the spread of fast-growing exotic trees such as Pinus radiata. Wetlands were drained, rivers were redirected, and the cleared land was turned into pasture and plantations. According to the Ministry for the Environment, by the early 2000s, only around 25% of the country was still covered by native forest.

Each part of the country experienced these changes differently. In the eastern parts of the North and South Islands—where the climate is drier and fires burn more easily—deforestation was faster and more complete. In contrast, the wet, rugged terrain of the Southern Alps and Fiordland helped preserve larger tracts of native forest. These areas today contain much of the country’s remaining biodiversity.

Forest fragments can still be found outside conservation lands—on hillsides, in gullies, and along farm edges. While easy to overlook, they play an important role in keeping native species alive and maintaining ecological resilience.