Operation Unthinkable: Churchill’s Secret Plan to Start World War III in 1945

Germany surrendered without conditions on May 8, 1945, leading to huge celebrations in cities such as London and Paris. After six years of constant fighting, millions were dead and many cities were destroyed, so most people thought the worst was over. Not Winston Churchill, though. Barely a week after the Nazis signed the papers, he asked his war staff to map out a possible assault on the Soviet armies that had settled into German territory. They gave it the name Operation Unthinkable, which captured the sheer audacity of the idea.

By 1945, the Soviets had turned Poland into their own backyard. Stalin brushed aside the Yalta deals on democratic elections. His soldiers stripped factories bare, locked up dissidents, and solidified their hold on the eastern bloc. Churchill understood his options were narrowing rapidly. American troops would soon ship out to the Pacific theater for the fight against Japan. British forces had already begun demobilizing. If action was possible, it needed to happen immediately while Western military power remained concentrated in Europe.

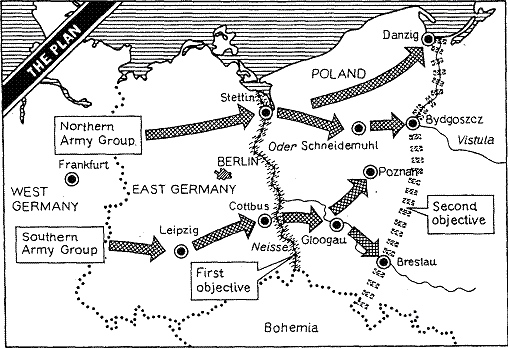

What the strategists proposed was downright risky. As of July 1, 1945, some 47 divisions drawn from British and American ranks, amounting to half the Allied presence left on the continent, would surge forward from near Dresden and punch holes in Soviet defenses. The wildest twist called for freeing captured Wehrmacht troops, outfitting them anew, and throwing them into the mix with British, US, and Polish fighters. Just like that, former foes would stand shoulder to shoulder against the Red Army.

The objective stayed clear-cut, drive the Soviets back across the Oder River, clear them out of Poland and eastern Germany, and dictate terms to Russia on behalf of the US and Britain, straight from the briefing notes. Churchill bet that a sharp offensive could drag Stalin back to the table for serious talks on Poland’s independence.

When the evaluation landed on May 22, 1945, it didn’t inspire confidence. The Soviets held a 2.5-to-1 advantage in divisions, which worsened to a 4-to-1 advantage for foot soldiers. They had rounded up around seven million men in total, with six million positioned in the west. A surprise start might give an edge at first, but the fight would probably bog down, worse yet if it lasted into the cold months. As seen in previous military campaigns, such as Napoleon’s failed 1812 retreat and Hitler’s failures from 1941 to 1945. Tackling Russia amid snow and ice has doomed plenty of armies.

Complications didn’t stop there. Would Truman back such a move? How could frontline troops accept Germans as comrades so soon after the surrender? And success in Poland wouldn’t cripple the Soviets anyway; they’d fall back, rebuild strength, and strike whenever it suited them.

Churchill scanned the document and wrote alongside it that tangling with the Red Army looked extremely doubtful. He soon labeled the whole thing a theoretical exercise at best. Plans for the strike got set aside.

Shifting focus, he wondered what might unfold if the Soviets rolled west after the Americans pulled out. That question birthed the defensive angle of Unthinkable. Analysis showed Britain couldn’t stand alone against a full Soviet thrust without major US involvement.

Before things could advance, the political landscape changed. Britain voted on July 5, holding off the count for ballots from soldiers abroad. Once announced, the results swept Churchill from power, bringing in Clement Attlee as the new prime minister. Operation Unthinkable vanished into storage.

As it turned out, the sequence of events fell into place nicely. The United States hit Hiroshima with an atomic bomb on August 6, followed by Nagasaki on the 9th, prompting Japan’s formal surrender on the 15th. World War II wrapped up entirely.

Britain withheld these files for over 50 years, only declassifying them in 1998. Their release showed how close the Allies came to another conflict following World War II. Ultimately, Churchill’s concerns about Soviet intentions in Eastern Europe proved accurate. Poland remained under Soviet influence until 1989, for more than 40 years.

Did word reach Stalin? Guy Burgess, planted in British intelligence as a Soviet mole, was active right then and could have fed them info. Accounts mention General Georgy Zhukov suddenly shifting Red Army postures in Poland to defensive setups that June. Mere prudence, or tipped off about Unthinkable? Stalin stayed mum, but it’s possible he geared up for precisely that threat.

Operation Unthinkable maps these days outline battles that stayed on paper, movements that never launched. They point to those critical turns in history where other paths could have reshaped everything. Churchill pushed for action, yet the risks loomed too large, and his defeat in the vote shut it down for good. We sidestepped that nightmare.

No attack materialized on July 1, Churchill’s exit buried the notion, and the Cold War took shape through tense talks, covert operations, stand-in wars, and the shadow of nuclear arms instead of head-on clashes. Seeing how 1945 teetered on the edge helps unpack why the years after played out the way they did.