Peoples of the Arctic

The Arctic region is home to diverse indigenous peoples who have inhabited the area for thousands of years. These peoples have adapted to the extreme cold, harsh environments, and unique challenges of the Arctic.

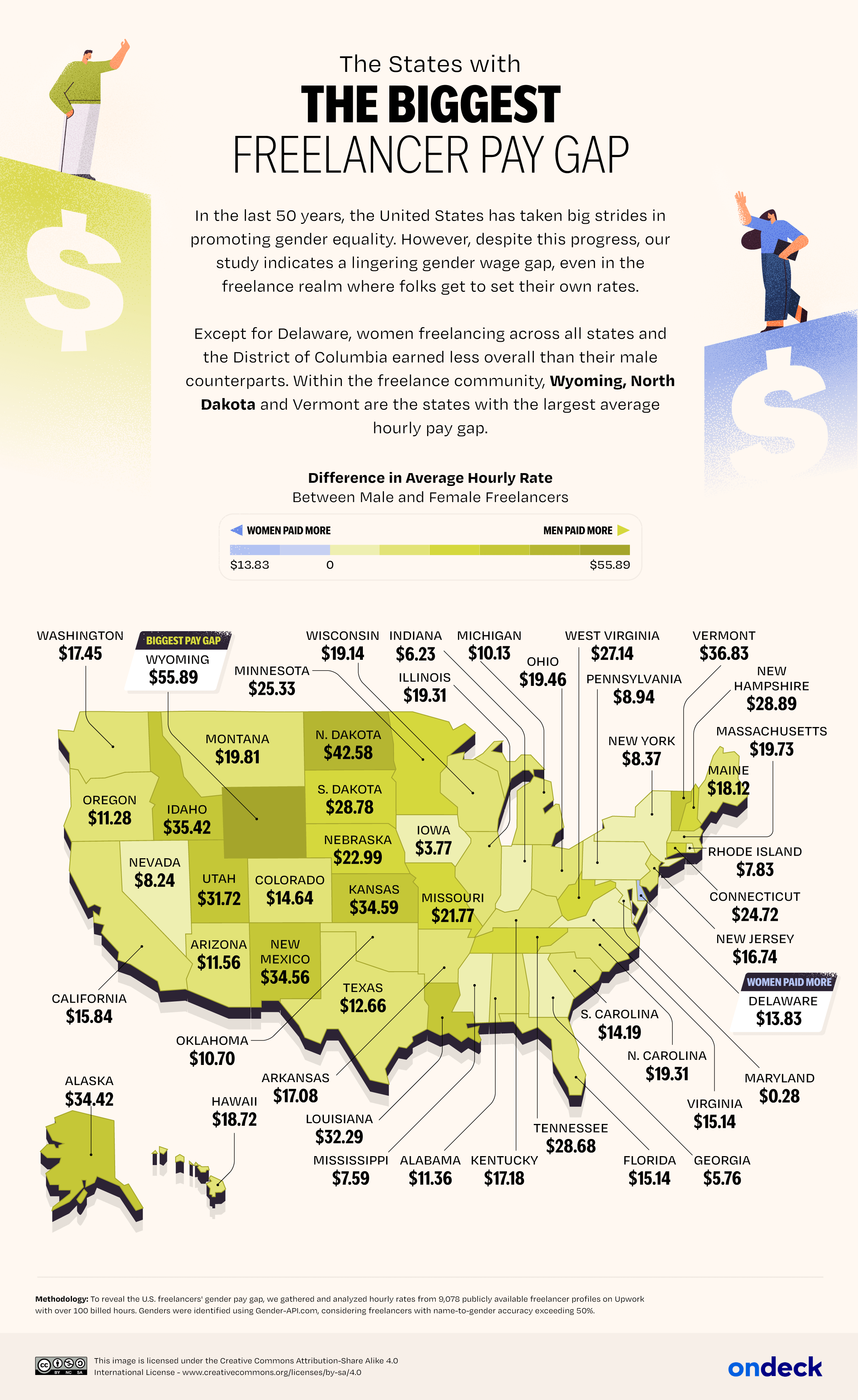

The map below created by National Geographic shows the most numerous ethnic groups of Arctic peoples.

Peoples of the Arctic

Who are they, these hunters and nomads along the ice-encrusted shores and frozen tundra of the Arctic basin? These tenacious men and women who, until recent times, wrested their livelihoods from the world’s harshest environment, who shaped rich traditions from a meager land? In the eastern or Old World Arctic, they were many peoples. Diverse in culture and language, they probably descended from hunting societies pushed north from Central Asia by population pressures near the end of the Ice Age, 10,000 years ago. In the western or New World Arctic, they are primarily one homogeneous people, speaking dialects of the Eskaleut language. Originally from Asia, they were already in Alaska at least 4,000 years ago and spread across the continent. Though they called themselves by several names, including Inuit in the east, the world came to know them as Eskimos. A few Indian tribes, whose forebears arrived thousands of years earlier, qualified as arctic peoples because they made seasonal hunting excursions north of the tree line – a better delineator of arctic ecology than the Arctic Circle.

The map shows tribal regions as they existed around 1825. By that time most of the indigenous people of mid-Canada, the last arctic region of Western exploration, had been contacted. Many northerners, on both sides of the Arctic Ocean, had experienced a long history of Western influence by 1825, but their native traditions in many areas would remain relatively intact well into this century.

Scarcity, in a word, describes the arctic ecosystem, where life-giving solar energy is in short supply. In winter the sun disappears for a long polar night of weeks, even months, depending on latitude. Six months later even the midnight sun – its rays prolonged but slanted – cannot thaw the frozen subsurface soil, or permafrost, that makes agriculture marginal at best. Precipitation is scant, and temperatures drop as low as minus 46°C (minus 50°F) in winter and seldom rise above 10°C (50°F) in summer. But more than cold itself, the paucity of resources for food, clothing, and shelter defined arctic life.

For most Old World arctic peoples, that life centered on reindeer. In earlier days the animals were hunted wild and tamed only to pull sleds. With the encroachment of gun-bearing European settlers and hunters in the 16th and 17th centuries, reindeer numbers declined. A

The New World reindeer, called caribou, was never domesticated and took second place to sea mammals as a resource. Though some inland groups sustained themselves on caribou, fish, and waterfowl, most Eskimos – coast dwellers – subsisted chiefly on sea mammals.

In addition to providing food for humans and sled dogs, seals – and to a lesser extent walruses and sea lions – supplied skins for clothes, boats, and summer tents; oil for the soapstone lamps to light and heat Eskimo homes; tendons for the thread; and bones as a substitute for wood. From kayaks and large, open, skin boats called umiaks, which Eskimos introduced to the world, they pursued the mighty whale with yet another native invention: the toggle-headed harpoon. With floats attached to exhaust the animal, the head stayed embedded in the whale, while the handle separated and fell away.

Though a master at adaptation, arctic man lived on the edge of survival. Prolonged severe weather frequently brought starvation. Diseases introduced by whalers and fur traders reduced whole societies to remnant populations. North of the tree line today, fewer than 100,000 indigenous people share their land with more than two million outsiders-mostly Russians and Scandinavians drawn to the north by its mineral wealth. In Soviet Siberia, reindeer breeding has been collectivized. In Alaska and Greenland, fishing has been commercialized. Meanwhile, arctic natives, whose ancestors faced the elements without reprieve, share a common hope-that the old traditions, adapted to the times, may survive.

North Alaskan

Rich in-game, fish, and sea mammals, Alaska’s northwest supported some two dozen Eskimo groups. The yearly catch of the bowhead whale, flensed with stone blades, provided bone supports for sod dwellings and food for months. Whale, seal, fish, and caribou meat was cached in permafrost or dried and stored on high platforms away from dogs.

Aleut

Brothers of the sea otter. Aleut men in skin kayaks sped through life-teeming waters around the Aleutians in pursuit of sea mammals—including whales, which they killed with poisoned spears. Waterproof seal-intestine shirts lashed to their kayaks kept hunters dry in spills. On their treeless islands, several families shared partially underground sod houses.

Kutchin

Epic walkers, as wore most subarctic Indians, the Kutchin trekked hundreds of miles every summer pursuing caribou beyond the tree line. In winter they wore superbly crafted snowshoes and lived in domed caribou-skin tents or log-and-moss houses. They traded furs to the Eskimos for white tooth shells from the Pacific shore. Strung with beads from while traders, this native money advertised a Kutchin’s wealth.

Central Canadian

The famous

Baffin Island

On this vast tundra island, several Eskimo societies inhabited coastal fjords, venturing Inland for caribou. Seals were caught at breathing holes in offshore ice by hunters standing vigil on caribou rugs. Hooded parkas were made with double layers of caribou hide, back to back, the hair facing out. So effective against the cold are hooded parkas that they are adopted by arctic visitors to this day.

Polar

World’s most northerly people numbered only 150 when discovered in 1818 in northwest Greenland. The use of bow and arrow and kayak had been lost during centuries of unusual cold when they were entirely cut off from all other peoples. Utterly without wood, they used sea-mammal bones for sled runners and for handles of nets for catching cliff-dwelling birds.

West Greenland

The most westernized of 19th-century Eskimos forged a hybrid culture from the ancient and the new. Keeping their communal houses of stone and turf, they adopted fabrics, implements, and some foods from 18th-century Danish missionaries and traders. Preferring guns for caribou hunting, these Eskimos retained traditions with kayaks and harpoons for year-round open-water seal hunts.

Lapp

Versatile as their land was diverse. Lapps, or Saami. pursued fishing, whaling, and even limited farming, thanks to the warming influence of the Gulf Stream system. On skis, which

Nenets

True Eurasians, the Nenets herded reindeer on both sides of the Urals and hunted seals and whales off the Barents and Kara seacoasts. In the 1870s tsarist Russia moved many Nonets to Novaya Zemlya to end Norway’s claims to the island. Drumbeating shamans – important figures everywhere in The Arctic – exorcised evil and foretold events. Prosperous herders often had two or more wives. whose tasks included setting up the conical tents and dressing skins.

Evenk

Herders of the largest reindeer, the Evenks rode their animals high on the shoulders, not on the weak backs. Like the Lapps, they also milked their deer. Wild reindeer, hunted from skis, provided most of their food. These skilled trappers paid heavy taxes of furs to the tsars as early as 1614. From the Yakuts, with whom they often clashed, they obtained Iron implements.

Yakut

Arctic latecomers, Siberia’s largest ethnic group migrated from as far south as the great steppes. Log houses and ironwork bespoke Yakut ties with the south, while their ancient tradition of horse and cattle raising was adapted to reindeer. Less communal than other arctic peoples, they developed near-feudal chiefdoms and private ownership of herds.

Indigenous Languages of the Arctic Circle

Between 40 and 90 Indigenous languages are used in the Arctic, depending on the techniques used to distinguish languages and dialects. Although many Arctic autochthonous languages are endangered, there is a growing tendency amongst Indigenous Peoples to establish actions that revitalize their languages. The Arctic is populated by an array of nationalities with diverse cultures and language groupings.

For this map, information was compiled on 89 boreal languages, which estimates for a little more than one percent of the world’s existing languages. These can be arranged into 6 distinguished language families plus 3 separated languages unrelated to any other language grouping.