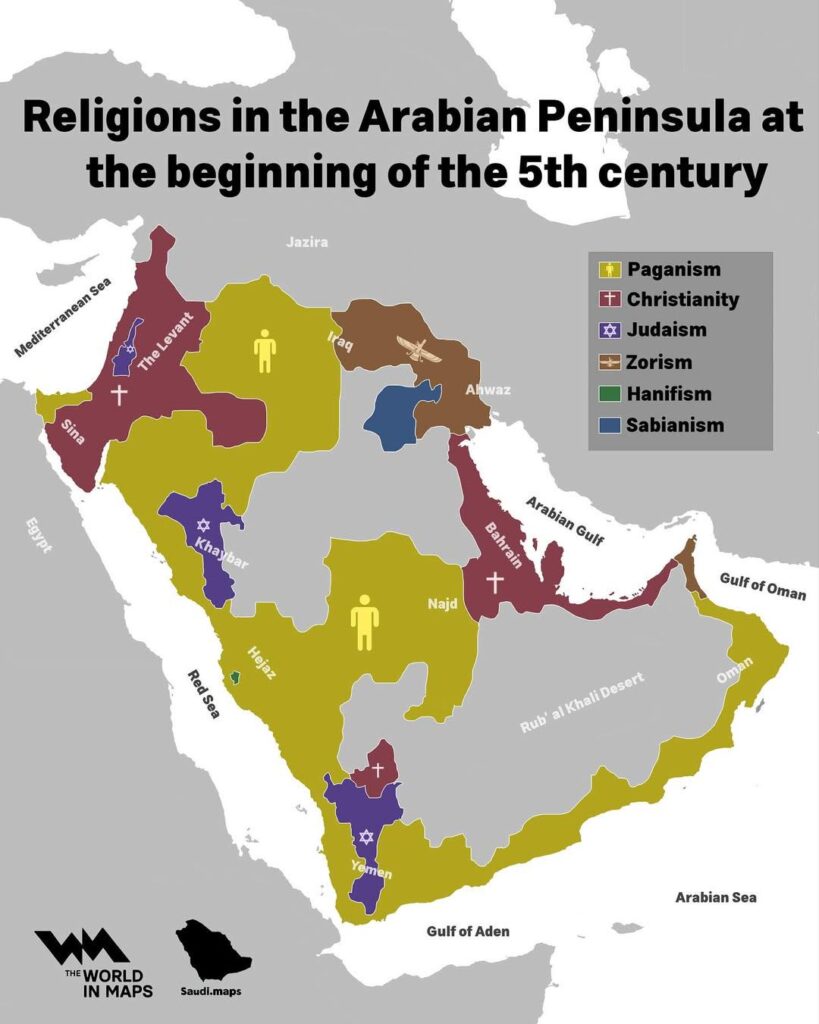

Religions in the Arabian Peninsula around the 5th century

Before Islam, the peninsula was religiously varied. Many people followed local, place-based polytheisms — shrines and clan gods that tied worship to a town, a caravan route or a sacred grove. Alongside those local cults you find individuals called hanifs, people described in later Islamic sources as monotheists who rejected idol worship and looked toward Abrahamic-style belief.

Nearer the great empires to the north and east, organized religions left clearer traces. Zoroastrian practice was strong in lands controlled by the Sasanian Persians to the northeast; while most Zoroastrian communities remained outside Arabia proper, cultural and religious ties crossed frontiers.

Christian communities were established in several coastal and inland towns. Najrān, for example, is remembered as a substantial Christian center in late antiquity with bishops, churches and recorded disputes that reached other Christian courts.

Jewish communities lived in a number of oasis towns and coastal settlements — Khaybar and pockets in Yemen among them — where Jewish families played roles in agriculture, trade and local politics for centuries before and after the seventh century.

Sabian or star-worshipping groups, especially around Harran and nearby Mesopotamia, are another element visible in the record; later Muslim writers sometimes grouped these communities with Mandaean or other local traditions.

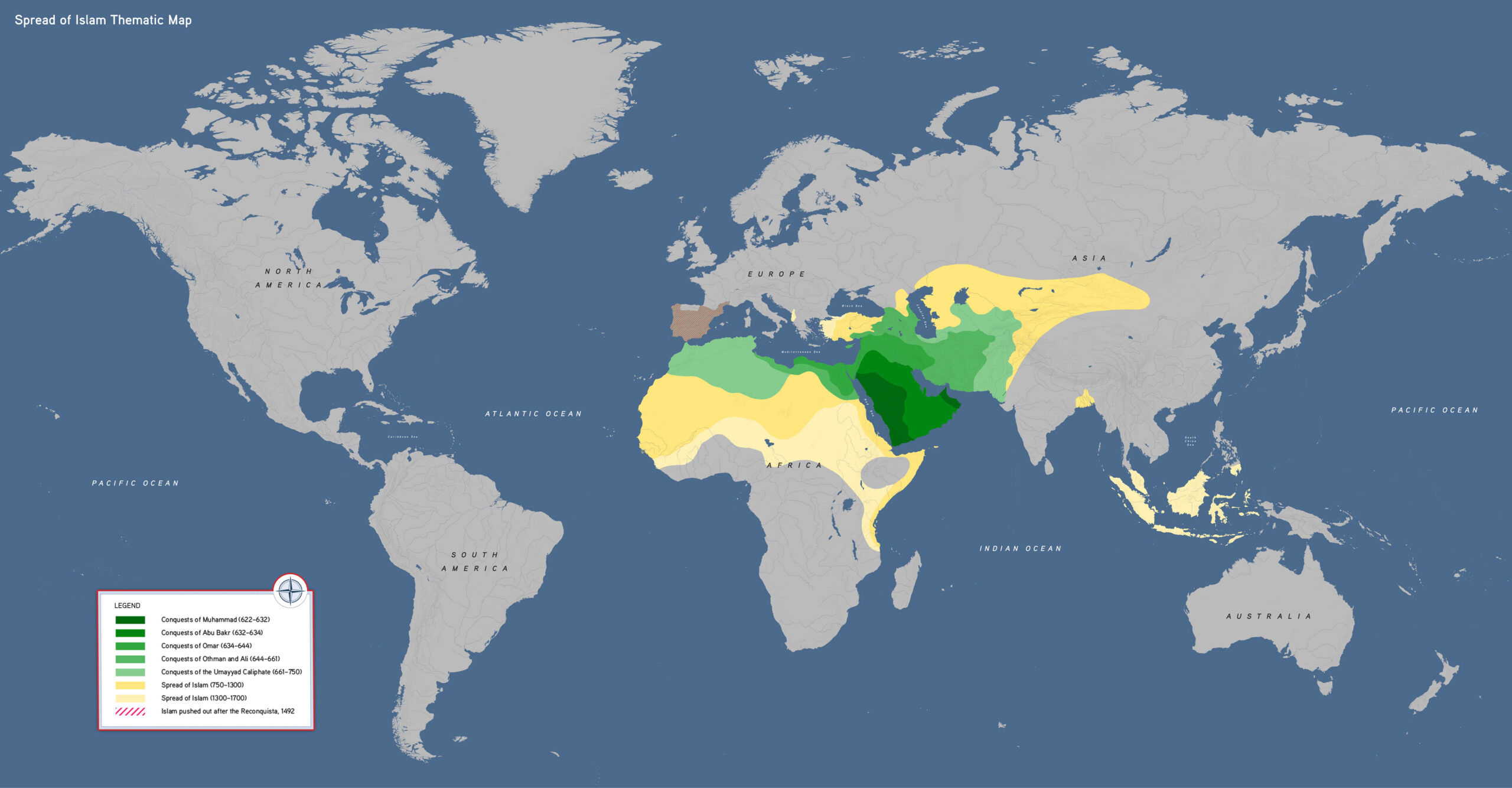

The religious map changed quickly once Islam began to spread. Islamic tradition dates Muhammad’s first revelation to about 610 CE and his migration to Medina to 622; by 630 Muslims had reentered Mecca, and within a few decades the early Muslim polity expanded across the Near East under the first caliphs. Political control, trade networks and social incentives all helped the new faith spread; in some places conversion followed state structures, in others it was more gradual and lasted generations.

Even after Islam spread across Arabia, older religions didn’t vanish at once — they found new ways to live on. In Persian lands to the northeast people kept Zoroastrian rites in family and community life, and when some groups moved westward they helped form the Parsi community on India’s west coast. In towns across the Levant and Mesopotamia, Christians still met in their churches and kept their worship and rituals alive even as political rulers changed. In Yemen and several oasis settlements, Jewish families stayed for many generations, and it was the large migrations and political turmoil of the twentieth century that greatly reduced those local communities.