Australia’s Expanding Deserts: Climate Maps from 1930 to 2099

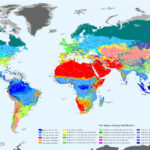

Australia is famously dry. Look at any climate map and red and orange dominate: hot desert (BWh) filling the center, hot steppe (Bsh) surrounding it. This isn’t a small feature tucked in a corner. It’s most of the continent.

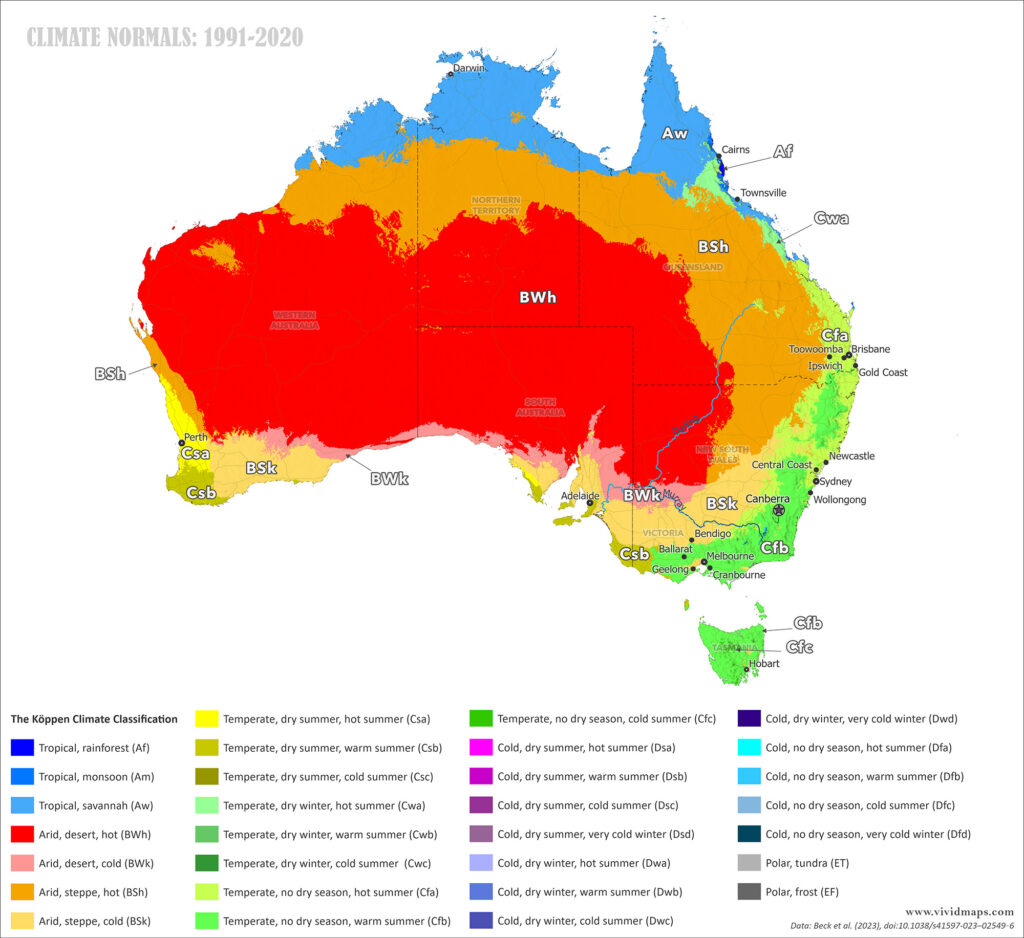

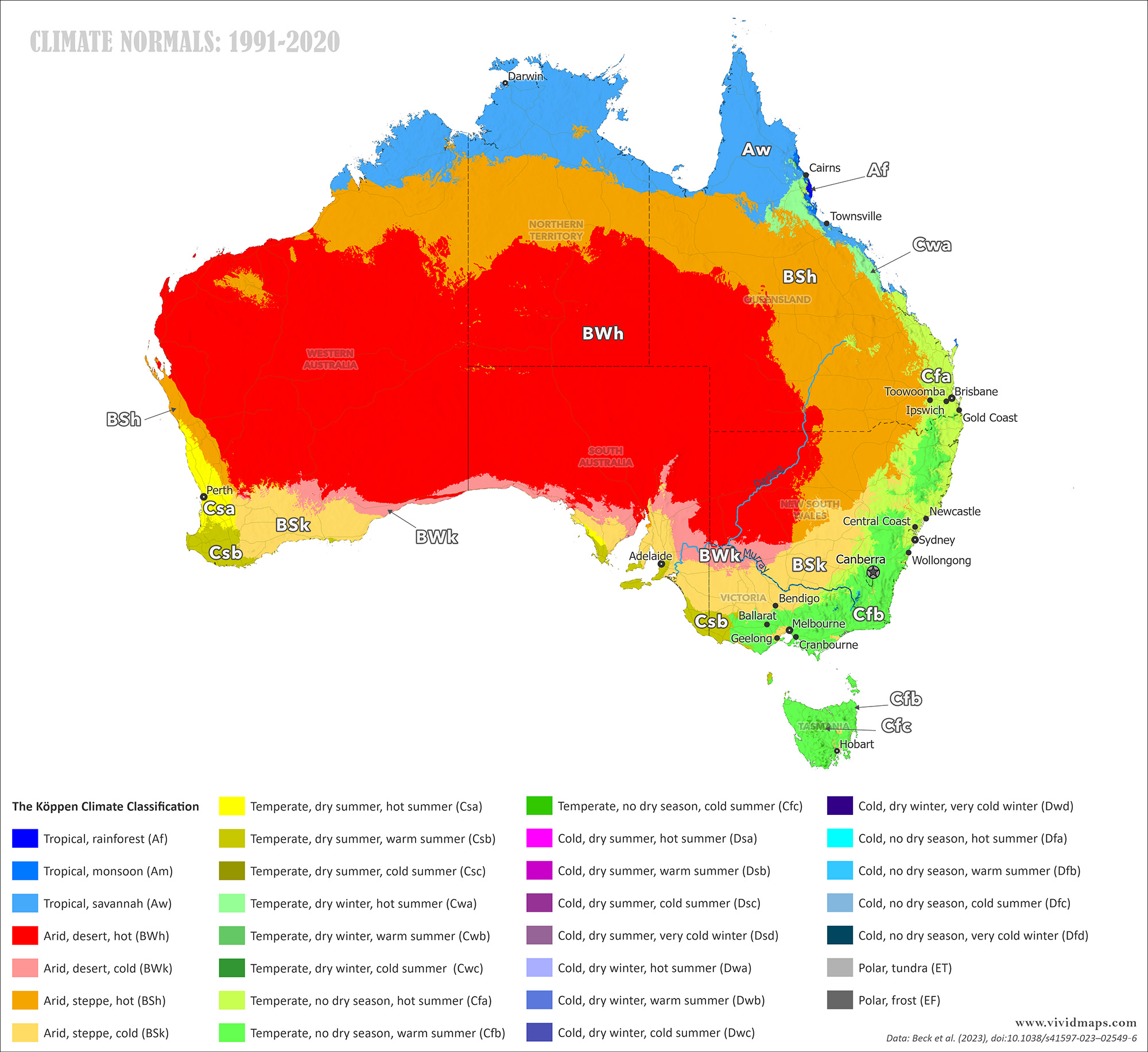

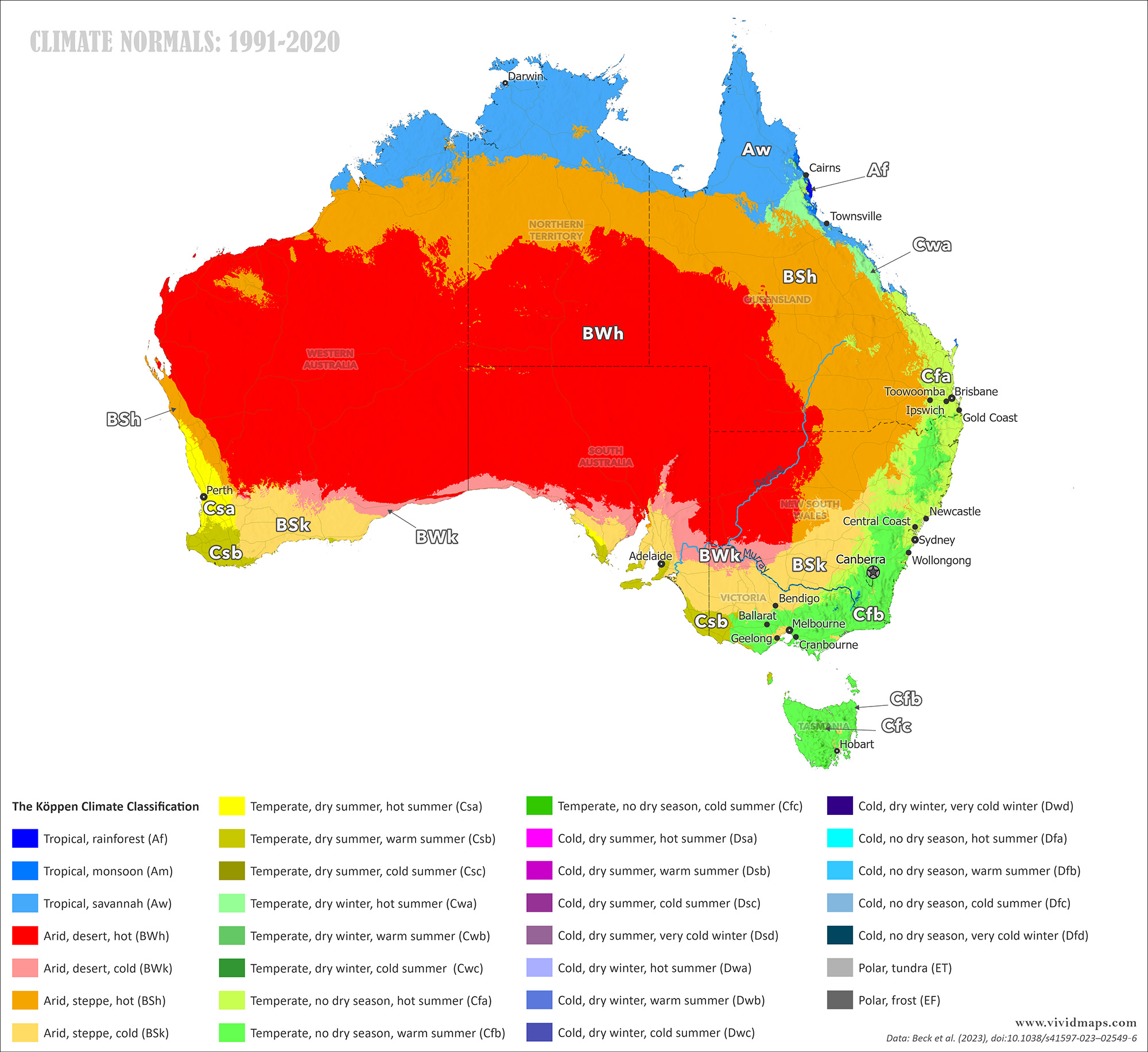

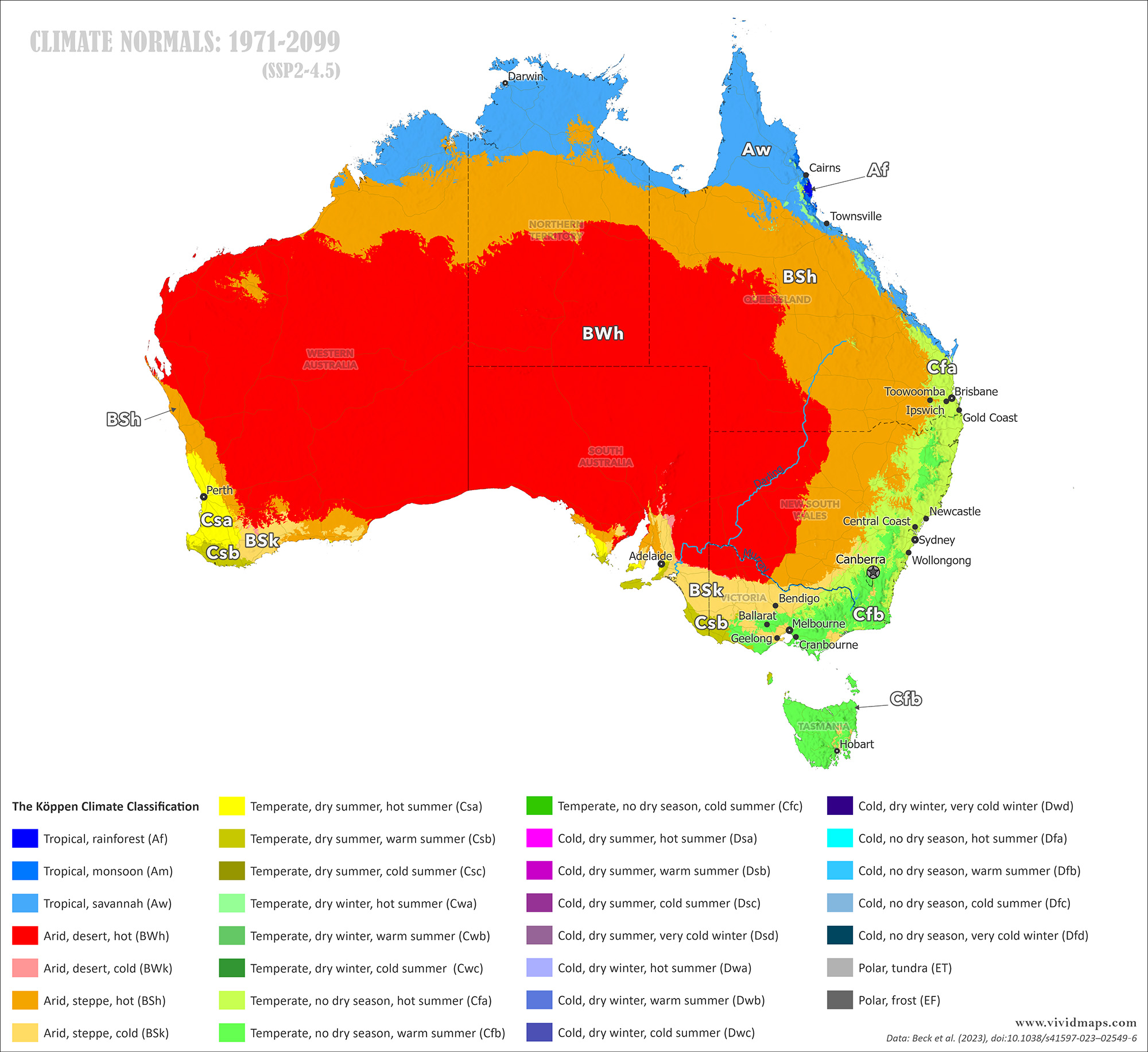

The population hugs the coasts. Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane line the east coast where oceanic and humid subtropical climates (Cfb, Cfa) deliver enough rain to support cities. Travel north and you’ll reach the tropics, featuring savannah (Aw) and rainforest (Af) throughout the Top End, where the monsoon dictates the seasons. Perth sits on the west coast in Mediterranean climate (Csa), sharing that weather pattern with California, the Mediterranean Basin, central Chile, South Africa’s Cape, and southwestern Australia. Tasmania gets oceanic climate (Cfb) with cool, damp conditions year-round, its mountains even cooler (Cfc). A narrow band of cold desert (BWk) runs along the southern coast, squeezed between interior desert and ocean.

I tracked how these zones have moved since 1930 and where they’re going by 2099 using data from Beck et al. (2023) at 1-kilometer resolution. The pattern: deserts spreading (for climate codes and their meanings, check my earlier post on global classifications).

Today’s map shows what you’d expect from the driest continent. Hot desert (BWh) dominates the interior in deep red. Hot steppe (BSh) in orange surrounds it. These two zones cover about two-thirds of the landmass.

The east coast concentrates Australia’s population. Sydney gets humid subtropical climate (Cfa): rain every month, hot summers. Northerly, between Brisbane and Townsville, you find patches of dry-winter subtropical (Cwa). Keep going to the north, and proper tropical climates take over: rainforest (Af), where rainfall remains heavy, and savannah (Aw), where the year is sharply divided between wet and dry seasons. Melbourne and the southeast have oceanic climate (Cfb) with moderate temperatures and rain spread throughout the year.

The south coast shows a thin strip of cold desert (BWk) trapped between the interior desert and the Southern Ocean. Perth has Mediterranean climate (Csa): summers dry out, winters get wet. South of Perth, that becomes warm-summer Mediterranean (Csb). Tasmania has oceanic climate (Cfb), with its central mountains cool enough to cross into Cfc.

A Century of Desert Expansion

The past century shows a consistent pattern: dry zones spreading.

Comparing the early 1900s (1901–1930) with modern times (1991–2020).

By the 1960s, hot desert (BWh) was already expanding, particularly toward the west coast. Around Perth, the Mediterranean and steppe zones (Csa, Csb, Bsk, Bsh) were getting pushed together as the desert grew outward. Hot steppe (Bsh) was pulling back slightly from the east coast.

By 1990, both BWh and BSk had grown larger. Bsh was advancing toward the east coast. BWh was pushing south, compressing the cold desert (BWk) belt along the southern coast into a narrower strip.

Today, hot steppe (BSh) has expanded both toward the northeast coast and in the opposite direction inland, taking over areas that used to be hot desert. The hot desert itself has moved along the southwestern coast, putting more pressure on the Mediterranean and steppe zones around Perth. The cold desert (BWk) running along the south coast has thinned noticeably.

Projections to Century’s End

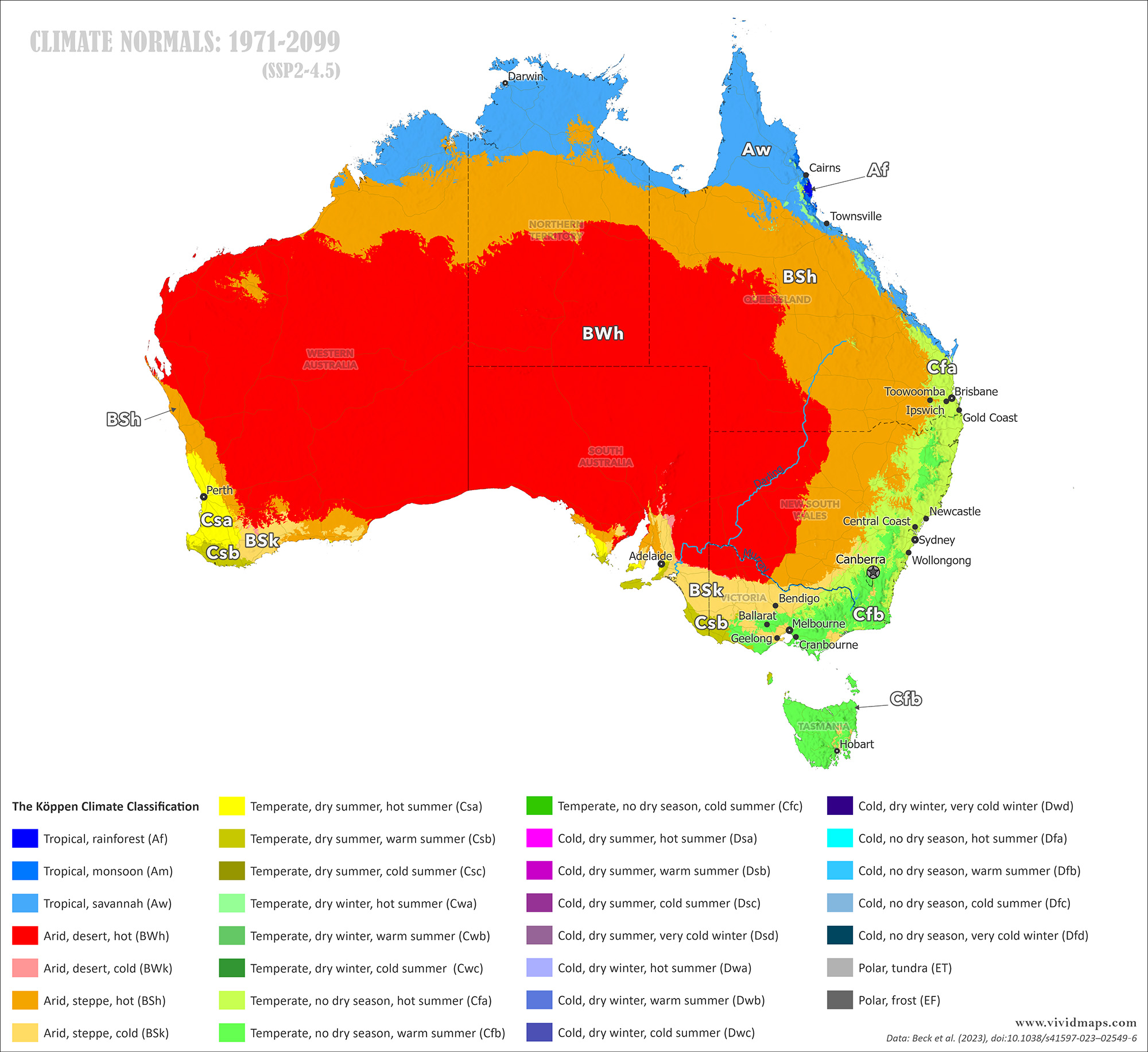

For future projections, I used the most likely ssp2-4.5 scenario where emissions plateau by mid-to-late century.

Today’s climate versus projections for the late 21st century (ssp2-4.5).

By the 2070s, hot desert (BWh) and hot steppe (Bsh) keep growing. The cold desert (BWk) along the southern coast is disappearing.

By 2099, the expansion accelerates. Hot desert and hot steppe push closer to the east coast where Sydney, Brisbane, and other major cities are located. They also encroach further on Perth’s Mediterranean climate zone along the west coast. The comfortable, habitable climate zones that support most of Australia’s population are getting compressed toward the coasts.

Over this timespan, interior deserts advance hundreds of kilometers outward. The expansion comes from multiple directions: pushing toward the east coast, toward the west coast, and south. Steppe zones advance toward the population centers on the east coast.

Major Australian cities are situated on the coasts because these areas receive adequate rainfall and experience moderate temperatures. When desert and steppe zones creep coastward, the consequences multiply. Water gets scarcer. Farmland becomes more marginal. Heat waves intensify. Fire seasons lengthen. The livable zones contract.

I also created maps for climate normals 1931–1960 and 2041–2070 as well. Here’s the full sequence: