Phantom Borders: How Poland’s Past Still Shapes Its Politics

Some borders disappear from maps — but not from memory. In Poland, the echoes of 19th-century partitions still ripple through modern elections. Though the German, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian Empires dissolved more than a century ago, their old dividing lines continue to influence how people vote — even in 2025.

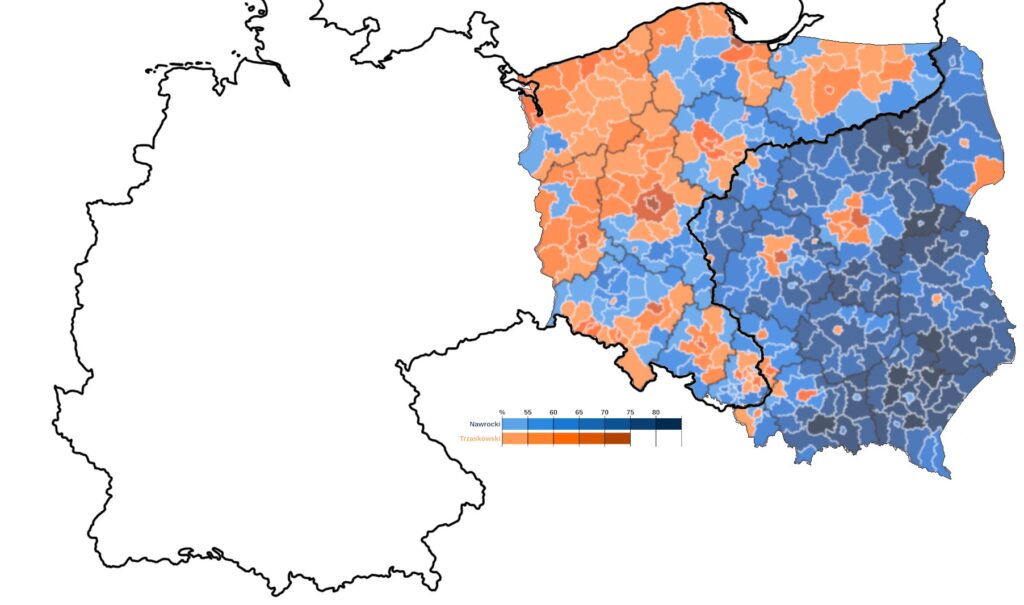

This first map shows the second round of the 2010 presidential election, colored by the winning candidate in each district. Orange indicates support for Bronisław Komorowski (Civic Platform, PO), while blue shows backing for Jarosław Kaczyński (Law and Justice, PiS). Overlaid on this electoral landscape is a faint but striking boundary — the former border of the German Empire.

And that’s when a pattern starts to emerge.

Komorowski’s base of support lay in Poland’s west and north — territories that once belonged to Prussia. These regions tend to be more urban, industrialized, and historically linked to Western Europe. Meanwhile, Kaczyński found his strongest voters in the east and southeast — areas formerly ruled by the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires — which remain more rural, Catholic, and socially conservative.

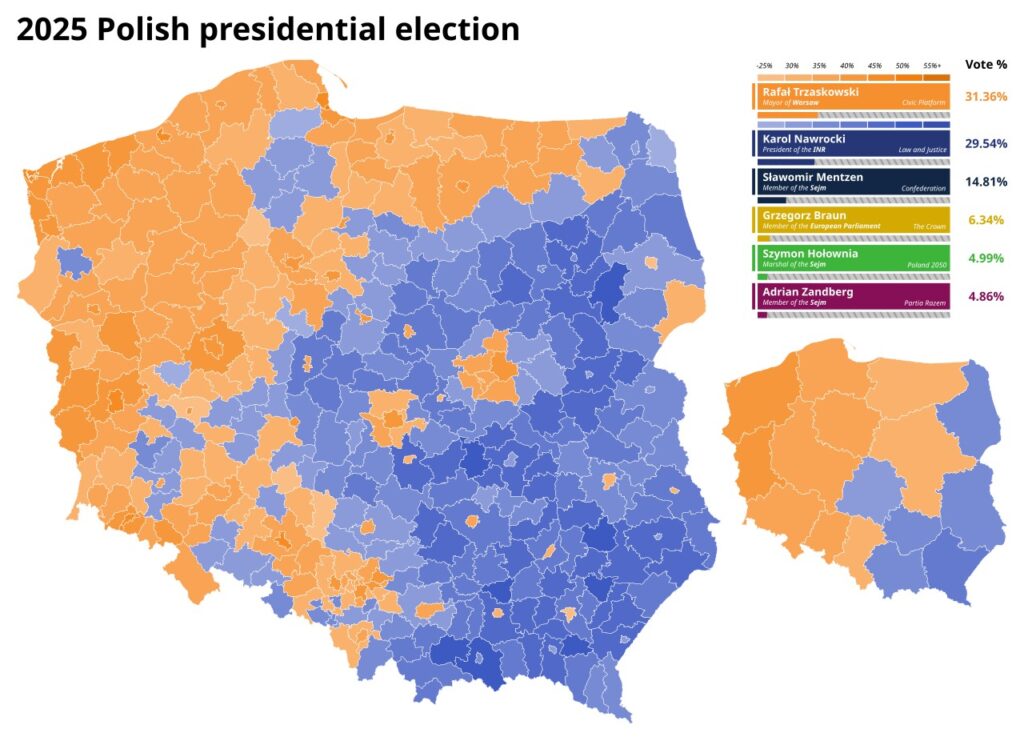

Fifteen years later, the electoral map has barely shifted. Once again, western Poland leans liberal and pro-European, while the east and south remain conservative strongholds. Where have these old imperial boundaries gone? They’ve vanished from every official atlas, yet somehow their political fingerprints remain etched across the landscape.

What you’re witnessing here is what scholars call a “phantom border” — think of it as the political ghost of empires past. These invisible lines continue to whisper in voters’ ears, shaping not just how people cast their ballots, but how entire regions develop economically and see themselves culturally.

Why does this imperial hangover persist so stubbornly? The answer lies buried in over a century of radically different governing philosophies.

Picture three neighbors raising children with completely different approaches. In the west and north — what we now call Pomorze, Wielkopolska, and Silesia — Prussian administrators ran a tight ship. They built cities, promoted industry, and pushed secular education with Germanic efficiency. Religion? Important, but not everything.

Move east toward Warsaw and the central heartland, and you entered Russian Poland’s sphere. Here, the Tsars played a different game entirely. Russification campaigns tried to stamp out Polish identity while Congress Poland limped along with limited freedoms and sluggish development.

Venture south into Galicia, and you’d find yourself in Austrian Poland — a world apart from both its neighbors. This was deeply Catholic countryside where tradition ruled and poverty ran deep. The Austro-Hungarians granted some autonomy, yes, but prosperity? That was harder to come by.

Here’s the remarkable thing: when Poland finally broke free in 1918, these regional personalities didn’t just disappear overnight. If anything, the tumultuous decades that followed — border shifts, population transfers, communist rule — seemed to cement these differences even deeper. What we see today on the electoral map is not just political preference — it’s the long afterimage of empire.