Europe’s Declining Cradles: Mapping the 2025 Fertility Crisis

What happens when a continent stops having enough children to maintain its population? Europe is finding out firsthand.

Last year’s UN estimates confirmed what demographers had been predicting: Europe’s population peaked in 2021. We’re now watching the beginning of what will be a long, steady decline—one that will reshape everything from pension systems to village life across the continent.

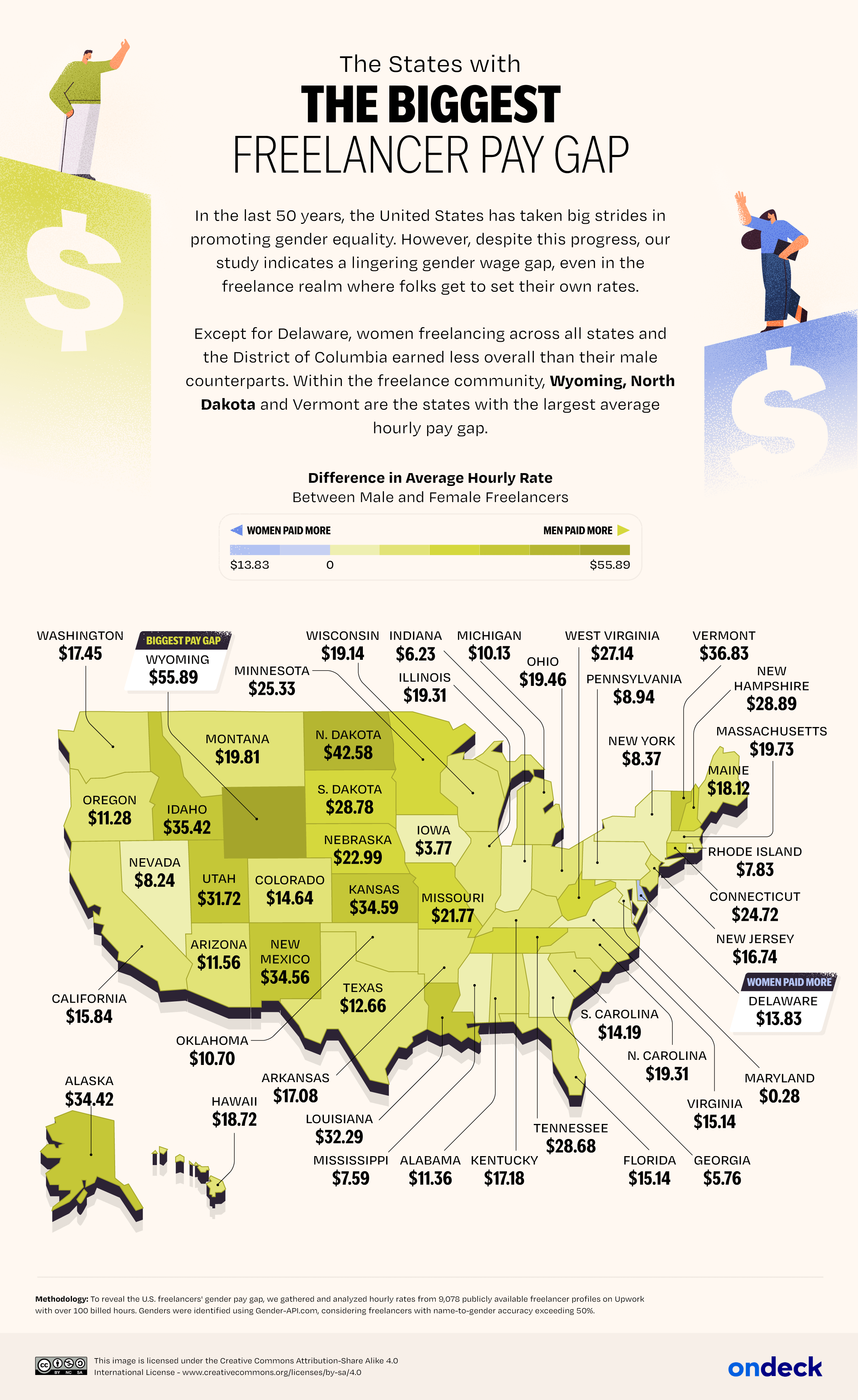

The map below captures fertility rates across European countries in 2025, and the geographic patterns are worth examining closely.

The 2.1 Threshold: Why Almost Everyone’s Missing It

Here’s the benchmark: 2.1 children per woman. That’s the fertility rate a population needs to replace itself naturally, without relying on immigration.

Looking at the 2025 map, only Monaco hits this mark at exactly 2.1. But let’s be honest—Monaco’s an outlier for peculiar reasons. With its high living standards, robust social policies, and wealthy population, it offers ideal conditions for raising children. Yet with only 39,000 residents, a few dozen extra births can swing the statistics dramatically. It’s less a success story than a statistical curiosity.

The rest of Europe? Everyone’s below replacement level:

Montenegro comes closest at 1.8. Bulgaria, Moldova, and Romania cluster at 1.7. France, Ireland, and Turkey hover around 1.6. Most of Western and Northern Europe sits between 1.3 and 1.5. Southern and Eastern Europe show rates that should concern anyone thinking about the continent’s future. Ukraine anchors the bottom at 1.0—one child per woman.

When the Slide Began

The fertility decline didn’t happen suddenly. Northern and Western European countries led the way, dropping below replacement levels in the 1960s. For decades, rising life expectancy and immigration masked the effects. But you can only delay demographic reality for so long. Forty years later, the math has caught up.

Southern countries like Italy, Spain, and Greece followed suit in the 1970s and 80s. Eastern Europe’s decline was more dramatic—the collapse of communism in the 1990s triggered sharp fertility drops across Ukraine, Russia, and the Baltic states. Political upheaval tends to make people reconsider starting families.

What’s Driving the Decline?

The reasons are tangled together, but here are the main threads:

- Later life stages. Europeans are marrying later and delaying parenthood, often until their 30s. In many countries, the average age at first birth now exceeds 30—which means fewer years of peak fertility for having additional children.

- Economic anxiety. Housing costs keep climbing while wages stagnate. Job security feels increasingly rare. In Southern Europe, youth unemployment remains stubbornly high. It’s hard to commit to raising a family when you’re not sure about next year’s income.

- The work-life squeeze. Even with progress on gender equality, many European women still juggle full-time work with disproportionate household responsibilities. Something has to give—and often it’s having another child.

- Cultural shifts. Parenthood is no longer seen as an inevitable life stage but as one option among many. That’s not inherently bad, but it changes the calculus around family size.

- Education effects. Higher education correlates strongly with lower fertility across Europe. Women who pursue advanced degrees often delay childbearing—sometimes past the point where they can have as many children as they might have wanted.

- Rising costs. The financial burden of raising children has grown substantially relative to incomes. We’re not just talking about direct costs like childcare and education, but opportunity costs—career advancement foregone, earnings lost during parental leave.

What Happens Next?

The demographic projections paint a concerning picture. By 2050, many Eastern European countries could see their populations shrink by 15-25%. The ratio of working-age people to retirees will tilt dramatically. Some rural areas face near-total depopulation—villages that have existed for centuries simply emptying out.

The economic ripple effects are significant: labor shortages across industries, pension systems stretched to breaking, shrinking domestic markets, potentially reduced innovation as populations age. Europe’s global economic position depends partly on having enough productive workers to sustain it.

Can Policy Change Anything?

Several countries have tried to boost birth rates through policy. France has comprehensive family support systems and maintains relatively higher fertility as a result. Sweden’s generous parental leave and childcare subsidies show some positive impact. Hungary has gone all-in with aggressive incentives—tax benefits, housing subsidies, loans forgiven after multiple children.

But here’s the catch: no European country has returned to replacement-level fertility through policy alone. The most effective approaches seem to combine financial support with structural changes—accessible childcare, genuinely flexible work arrangements, cultural shifts in how we consider gender roles and caregiving.

Immigration offers the most straightforward solution to population decline in the near term, though it brings political and social complications. Germany has managed to offset natural population decline by maintaining relatively open immigration policies, but this approach faces resistance in many countries.

Three Paths Forward

Europe likely needs a combination of strategies: policies that genuinely support families, immigration systems that work, and perhaps new economic models adapted to smaller, older populations. Each country will need to find its own balance based on its circumstances and values.

The question isn’t whether Europe’s population will decline—that’s already happening. The question is how societies will adapt. Will we see ghost villages in Eastern Europe alongside diverse, crowded cities in the West? Can pension systems survive without fundamental restructuring? How do economies function when the population pyramid inverts?

What changes have you noticed in your own community around family size and attitudes toward childbearing? Do you consider policy interventions can make a meaningful difference, or is this demographic shift inevitable? I’d love to hear your perspective in the comments.

Hallo,

How can EU survives without above 2.1 fertility rate? why is everything more important? Is anybody worried? ……

I think the only realistic path forward is through immigration, since family support policies in many countries simply aren’t working effectively enough to reverse the trend.